AMES, Iowa -- They're calling it Cyclodrome. And deep in the bowels of Iowa State University's College of Design, the 15 architecture graduate students are working at a frenetic pace to build it. Even though they had never before seen, ridden or even heard of a velodrome. Even though no plans or dimensions existed to guide them.

But the nation's smallest velodrome should be ready to roll in Des Moines on July 8. That is, if all goes according to schedule. And if their math is right, their angles are straight, their transitions are smooth and their connections are strong.

The students -- none were architecture majors as undergraduates -- are in Associate Professor Jason Alread's intensive "Service Learning" summer course. Students learn how to use modest means to design and build things for a nonprofit. It's a bit of a summer boot camp that helps turn non-architecture majors into architects.

"We tend to have architecture students do drawings and models and build things at a small scale," Alread said. "This class gives them the opportunity to deal with real materials at full scale and an actual assembly process. You learn a lot when you have to translate from the small model into a full-scale object."

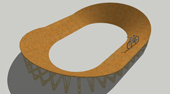

The class is building a mini-velodrome for the Des Moines Bike Collective, a nonprofit organization that promotes bicycling in Central Iowa. A velodrome is an arena with a banked track for cycle racing. The pint-sized, mini-velodrome will be portable and used for demonstrations, teaching and fun events.

Alread came up with the project idea with his longtime cycling friend Kim West, who is associated with the Bike Collective. The organization provides low-cost and free bikes to people in need, creates and distribute trails guides and generally tries to "raise the profile" of cycling. They will use the Cyclodrome for educational and fun outreach events that promote bike riding.

"I've been pitching this idea to people for years," West said. "There is a dearth of tracks in the Midwest. The Cyclodrome will help us generate interest in eventually getting a full-sized track."

Full-sized velodromes have a track run of about 250 meters -- The Cyclodrome will be about 25 meters. It will measure 24 feet by 34 feet on the outside, with an infield of 10 feet by 20 feet.

Architecture grad students

Mike Thole (left), Manchester, and Shzamir Garcia, Puerto Rico.

Photo by Bob Elbert.

Architecture grad students

Mike Thole (left), Manchester, and Shzamir Garcia, Puerto Rico.

Photo by Bob Elbert.

Building it is nearly a full-time job: students work in the woodshop or the assembly space for as long as six hours each day. Fortunately, they brought to the project a diversity of experience with degrees in art history, interior design, sculpture, physics, engineering, woodworking, language studies and landscape architecture. And it's all coming in handy for this project.

They figure out coefficients of friction, calculate angles, determine slopes and calculate loads. They test materials and finishes. They measure spans and count trusses. They cut two-by-fours, drill fasteners, add glue and start over. Fifty-two trusses. The result is a series of extremely sturdy structural members, able to take the forces that will be applied to the track.

So far, the class has learned that turning square pieces of flat plywood into curved, angled pieces of track is no easy matter. The shape is much more complex than it looks.

They started with a drawing, built a model, identified design problems, then built a prototype of one section: The most challenging part of the track, which is at the transition between gently sloped, straightaway and a sharply angled turn. (It's essential that the transition is precise and balanced to ensure rider safety at the curves.) Next, the students started construction of an entire section--one-fourth of the Cyclodrome. If that is successful, they'll replicate exactly what they have done three more times.

"Limited-scale projects like this one let students build something at full scale for an actual client with a real deadline and budget," Alread said. "They have to deal with variables not found in a regular studio. If the client doesn't like it, or something doesn't turn out as expected, they have to make the changes necessary for it to work."

And just this week, the students encountered a glitch. That pesky transition wasn't as smooth as it needed to be. You can read about how they modified the track to get a smooth ride on their blog http://cyclodrome.blogspot.com/