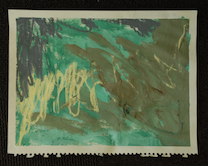

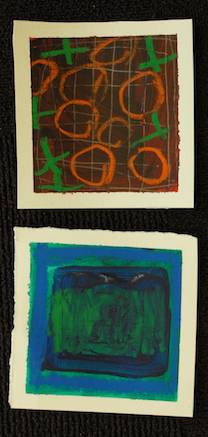

"When I look at these paintings I see John's voice," says Debra Satterfield, associate professor and interim chair of graphic design, with paintings by her son who has epilepsy and an autism spectrum disorder. Photo by Bob Elbert. Download here.

AMES, Iowa —What started as a school project for her cognitively disabled son has turned into a career focus for one Iowa State University graphic design professor.

Debra Satterfield's teenage son, John, has epilepsy and an autism spectrum disorder. A few years ago, when his school assigned a project from a list of suggestions, she decided John would try painting. Not only did he enjoy it, he became engrossed in it. He approached it purposefully. And he was good at it. One of his paintings won a prize at the Iowa State Fair — and none of the judges knew he was disabled.

"It was eye opening to me. I had never even thought to give him a chance. When I look at these paintings I see John's voice," Satterfield said.

"It made me wonder how many others like him could benefit from having a creative outlet," she said. "Everybody deserves the opportunity to express themselves."

Since then, Satterfield, associate professor and interim chair of graphic design, has pursued that line of thinking in her teaching, research and outreach projects at Iowa State. She works with a team of faculty and students on the design of educational, social inclusion and play experiences for children with cognitive disabilities, including autism spectrum disorders.

In two recent studies they've surveyed two groups: college students with ASD traits, and parents and teachers of children with cognitive disabilities. Now they're putting their research findings into practice, piloting innovative workshops for kids with cognitive disabilities and autism.

These kids grow up

Satterfield; psychologist Christopher Lepage, Sutter Neuroscience Institute, Sacramento, Calif.; and Nora Ladjahasan, assistant scientist in Iowa State's Institute for Design Research and Outreach, recently returned from the International Annual Meeting for Autism Research. The team presented two research posters to doctors, psychologists and other medical professionals who study autism.

One research project looked at the potential presence of ASD in the online college community and considered methods of online educational content delivery. The second study presented compared perceptions of parents and teachers of children with autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders regarding the importance of specific skills.

"According the Centers for Disease Control, 1 in 88 live births are on the autism spectrum. So, high-functioning ASD children grow up and will be involved in every aspect of society," Satterfield said. "As a designer, the question 'how do I design better quality information, products and services' is always in my mind. And it comes back to better understanding the audience."

How do they like to learn?

After Satterfield's graduate students had researched ASD for a project, some told her they identified with a few traits of people diagnosed with high-functioning autism. She decided to find out more about the educational needs of college students with personality traits associated with ASD.

In the small pilot study, students (from both a traditional, on-campus graphic design course and an online human computer interaction course) answered a questionnaire about their preferences for course delivery, assignment types and evaluation techniques. They also completed a well-known, self-reporting tool -- the Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised.

The results showed 21 percent of the students scored above the diagnostic threshold for ASD on the scale, and 79 percent were below. The human computer interaction students tended to score higher on the scale than the design students. And all who scored above the threshold were from HCI.

Those below the diagnostic threshold (no ASD) preferred face-to-face lectures with personal interaction, selecting their own topics for research and group assignments, and designing, constructing and presenting product prototypes for their evaluations.

Those above the diagnostic threshold favored video-recorded or online course delivery with no personal interaction with students or faculty, topics assigned by the professor, and projects with flexible timeline and completion dates. For evaluations, they favored taking tests, or using phone or Skype discussions with the professor.

"Because of the prevalence of ASD in the general public, and the fact that many are highly intelligent or talented in areas valued by some disciplines, educators need to be able to develop curriculum that optimizes their strengths," Satterfield said.

What skills are most important for them?

In the second study, the researchers surveyed parents and teachers of children with ASD on their views about how the children are impacted by skills involving language, social interaction, behavior and technology use. They wanted to determine if these issues were important to both groups. Results indicated that both groups see all areas as extremely significant. A second phase will ask them to rank the relative importance of these skill areas.

"By combining these two studies, we know that even the skill areas that are ranked as least important are, in fact, very important," Satterfield said. "This will guide future product and service design for persons with ASD, and will allow us to address these issues in a meaningful and well-informed way."

Serve the child, serve the community

Satterfield at pilot creativity workshop at ChildServe. Photo by Alison Weidemann.

Satterfield and her colleagues are working with ISU Extension and Outreach to pilot workshops for children with cognitive disabilities at ChildServe, a not-for-profit organization that partners with families to help children with special needs. ChildServe provides specialized pediatric health care services, and offers accessible, family-centered care unique to each child.

Gleaning insight from their previous studies, as well as Satterfield's own experiences with her son, the researchers are developing activities that safely allow the children to explore creativity and communication activities. They want to help the children increase their ability to communicate using sensory, tactile and visual methods, and to identify the children's skill areas.

"We've observed the children in their activities at ChildServe. We look at markers of engagement, satisfaction or quality -- for example, if there's better eye contact, or higher vocalizations," Satterfield said.

"I don't know if all these kids will become artists or designers, but we can at least give them the chance to try and express themselves,” she said.

Once they have the model for how an educational institution can partner with a facility like ChildServe, then the team can replicate and disseminate it.

Satterfield also wants to explore the possibility of displaying the children's artwork in the community.

"It's important for the parents of these kids to have some kudos coming back to them. Nobody is telling them that their child is talented or gifted or has value," Satterfield said. "When you serve the child, you're also serving the family and the entire community."