AMES, Iowa -- Iowa is the national center of an ethanol plant construction boom. There are 27 plants currently processing corn, mostly for ethanol, and as many more either under construction, planned or proposed.

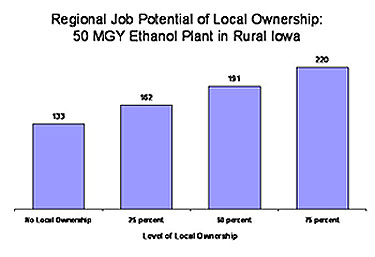

But what does a new ethanol plant really mean to a local economy? With no local ownership, the plant would either create directly or otherwise stimulate a total of 133 jobs in the regional economy -- with 29 more jobs being created for every 25-percent increase in local ownership of those plants -- according to a new study by two economists from Iowa State University.

"What that means is that we have local ownership receiving dividends and they're turning around and spending some portions of those dividends back in the local economy. They're buying consumer goods, and also doing some business spending," said David Swenson, an associate scientist and lecturer in economics and community and regional planning at Iowa State and lead author of the study. "What I always tell my classes is that any dollar that leaves our community has a hard time coming back, but a dollar that stays in our community has a multiplier effect."

Swenson joined with Liesl Eathington, assistant scientist and staff researcher in economics, in authoring a research paper titled "Determining the Regional Economic Values of Ethanol Production in Iowa Considering Different Levels of Local Investment." Jill Euken, an industrial specialist in bio-based products from ISU Extension/Center for Industrial Research and Service, assisted in information gathering. ISU Extension Professor of Economics Robert Jolly also shared his existing research on ethanol plant costs and returns for this study. The research was funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation through the Bioeconomy Working Group at Iowa State University -- a project overseen by ISU's Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture.

Constructing the model

The researchers created a modeling system that considered the job growth potential to a rural area of Iowa for an ethanol plant producing 50 million gallons per year, given different levels of local ownership or investment. To build the model, they acquired, developed and processed information on the production characteristics of modern ethanol plants. The 2002 U.S. Census of Manufacturing ethyl-alcohol sector allowed them to understand some of the basic characteristics of production -- including jobs, payroll, and benefits. They also used data compiled in the National Income Product Accounts maintained by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

"These data are not easy to come by, and this analysis relied heavily on research and outreach originating from both the University of Minnesota and at Iowa State University to determine the production characteristics of modern ethanol plants," wrote the researchers.

Once the data was obtained and modified, a simulation modeling system was developed to test the consequences of different ownership configurations. All of the modeling was conducted simulating new plants in a study region consisting of three major corn-producing Iowa counties that currently do not have ethanol plants.

"The baseline amount assumes that there is no local ownership -- that the plant is totally externally owned," said Swenson. "We then allocated the returns to investors back into the county to mathematically model how the county's economy would react to an increase in that kind of income. In particular, we were interested in the boost in jobs that would accrue."

"These values vary depending on the area of the state that we are studying and the extent to which a local economy is developed," he said. "After developing the model, we applied it to four actual ethanol plants currently in operation in Iowa."

Real applications to Iowa ethanol plants

Four Iowa plants were studied to demonstrate the region-wide economic impact of these plants, given their actual local ownership amount. The researchers determined the local ownership by using zip codes and share amounts of investors within the primary corn market area that was benefited by the plant. One was completely externally owned, with the local ownership of the other three was 27 percent, 63 percent, and 73 percent. They arrived at the following conclusions:

- For the firm that had 27 percent local ownership, the local ownership dimension accounted for 47 more jobs.

- For the firm at 63 percent, the local ownership dimension added 80 more jobs.

- For the firm at 73 percent, the local ownership dimension added 53 more jobs.

"While these values vary by level of local ownership and the overall characteristics of the local economy in which the individual plant resides, higher levels of local ownership yield higher job impacts for rural areas -- so long as returns to investors are robust and competitive with other investment alternatives," said Swenson.

"It is important to remember, however, that the econometrics in these modeling exercises work in reverse," he said. "Losses in plants that are locally owned resulting in sharply reduced or no payments to investors will be felt as job losses in regional economies, and those losses will be numerically greater in areas with higher local ownership."

The paper is available online at http://www.valuechains.org/bewg/Documents/eth_full0706.pdf. A summary of the study is also available at http://www.valuechains.org/bewg/Documents/eth_sum0706.pdf.