AMES, Iowa -- A Veterans Day observance at Iowa State University will honor four former students who served and died in military service -- one from each major conflict of the 20th century. Their names are engraved on the walls of the Gold Star Hall, the war memorial in the university's Memorial Union.

One was a soldier from Ames, Russell Manning Vifquain (VIF-kin) Jr., who died in World War II.

Former students are eligible for name placement in Gold Star Hall if they graduated from or attended Iowa State full time for one or more semesters, and died while in military service in a war zone. As names become known, they are added to the wall and the soldiers are remembered in the Gold Star Hall Ceremony on Veterans Day.

Iowa State is able to memorialize Vifquain this Veterans Day thanks to the help of his sister, Elaine Vifquain of Ames, who shared remembrances. Kathy Svec, retired ISU Memorial Union marketing director, researches each person through local newspapers, genealogical and historical societies, yearbooks, phone directories and online resources to track down family members and piece together each soldier's life story.

Growing up in Ames

Vifquain was born in Ames on April 1, 1918, the first of four children born to Zola and Russell, an agronomy professor at Iowa State. The family lived west of campus on Forest Glen.

1936 high school

graduation

1936 high school

graduation

In high school, Vifquain was involved in activities and sports, developing real skills on the golf course. A member of Ames High's first golf team, he earned medals his junior and senior years. In 1934, he won the Ames City Golf Championship.

Golf champ to airman

After graduating in 1936, Vifquain entered Iowa State in engineering and pledged Phi Delta Theta fraternity. Known as the blond "demon of the fairways," he continued golf and was on the 1939 Big Six golf championship team.

With war and the draft imminent, Vifquain left Iowa State in spring 1940 and volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Later that summer he went through a 12-week school in celestial navigation at the University of Miami. He was in the first class of 44 navigators to be trained by Pan American Airways for the Air Corps. They learned aerial navigation and weather forecasting.

1940

celestial navigation school graduation

1940

celestial navigation school graduation

Commissioned as a second lieutenant in April 1941, his initial order to go to the Philippines was cancelled with the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was re-routed to Alaska in the first B-26 bomber group.

North to Alaska

During World War II, Alaska was one of the most strategic places because the Aleutian Islands offered the most direct invasion route to Japan from the west coast. Vifquain spent 18 months there as a member of one of the first squadrons to land and operate from the advanced base on Adak Island. He flew 30 bombing missions through bleak, frigid and foggy Alaskan weather. On June 4, 1942, he participated in an attack against enemy naval concentrations that received heavy anti-aircraft fire. Vifquain received his first Air Medal for the raid. He was able to go home for Christmas in 1942.

Volunteering for the Pacific

The following March, he was promoted to captain and decorated with the first Oak Leaf cluster to his Air Medal for bravery under tough flying conditions. In May, Vifquain's 77th Bomb Squadron was sent back to the states to rest. He was assigned to a series of airfields and, by that time, was eligible for a discharge. But Vifquain was nominated to join the B-29 Super-Fortress group, and volunteered for an extra tour of duty in the Pacific.

B-29 Navigator

B-29 Navigator

On Nov. 18, 1944, he went to the Marianas with the first B-29 group. Known as "the mightiest aerial weapons" of the war, B-29s were designed to fly very long distances to attack Japan. They were equipped with armor, leakproof fuel tanks and heavier guns. Reaching speeds faster than 300 mph, B-29s operated distances in excess of 1,000 miles at sea.

Tokyo missions

A week later, the bomber command launched the first of many daylight-bombing missions over Tokyo industrial sites -- a 3,000-mile roundtrip. Flying over the ocean during daytime made navigation extremely difficult without mechanized instruments or visual cues on land. Everything was done by sextant.

B-29 crew flew

1,500 miles on two engines

B-29 crew flew

1,500 miles on two engines

The B-29 Vifquain navigated made it to Japan, but limped 1,500 miles home on two of four engines. This feat was hailed as "a magnificent achievement" because two engines were not designed to fly that kind of a load and had never flown so far. To keep the plane in the air, the crew stripped the interior and threw out parts.

On April 1, 1945, Vifquain was promoted to major and later that month received the second and third Oak Leaf clusters to his Air Medal.

Ready for that desk job

In what was to be his last letter home, written on May 12, 1945, he said, "They have set up a new training center for B-29s at Tucson and guess it has developed into a big project. Think a desk job there would suit me fine."

Two days later, he prepared for his 17th B-29 mission in which he would be lead squadron navigator for 500 B-29s. They departed from the Marianas at midnight for the five-and-a-half hour flight to Nagoya. Although Vifquain's plane had early indication of trouble in the number one engine during the first climb, the plane made 16,000 feet and proceeded. About 25 miles inland, the number four engine malfunctioned. The plane left formation and ditched its bombs, but one jammed the bay door. Conditions on board were serious.

Saving his crewmates

Navigator's area

Navigator's area

Vifquain established their position to be about one hour's flying time to the tiny island of Iwo Jima. The crew did not expect to keep the plane aloft the 700-mile distance. Because of weather conditions, accurate navigation was all but impossible. According to a crewmate, Vifquain did a "miraculous" job of pinpointing Iwo: "With any other navigator, none of us would have made it that day."

But clouds were low and visibility poor, making a landing impossible. The commander gave the order to bail in hopes of being able to do so over land or near a destroyer. Radio contact was made at Iwo Jima. The number three engine malfunctioned, but the plane limped on. When the number one engine caught fire, all were ordered to bail. It was about noon.

All 12 onboard bailed and the plane exploded 10 seconds after the last was out. Vifquain left the aircraft through the forward wheel well, and crewmembers thought he cleared the plane. The clouds were so thick, however, they could not see one another or tell if they were over water or land.

Missing in Action

Two nearby ships were alerted. Some crew landed on the island, others in the water up to seven miles from shore. Ten were rescued. Vifquain and one other who landed in water were lost. Rescue vessels searched for 48 hours before, during and after the storm that rolled in, but to no avail. Vifquain was eventually declared dead. His body was never found.

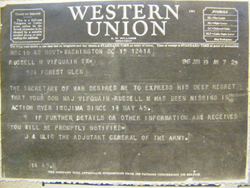

MIA telegram to

family in Ames

MIA telegram to

family in Ames

Dick Budington, the radar operator, wrote that he and "Vif" had lived together and flown most of their missions together, "Vif was my closest friend out here and I owe my life to him -- together with the rest of us who were picked up."

Vifquain's story and those of all the members of that first 1940 Navigation School class have been recorded in "On Celestial Wings," a book by class member and former Indiana governor, Col. Edgar Whitcomb.

Highest honors

In addition to his Air Medals, Vifquain was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the highest award given to a member of the military after the Medal of Honor. The Purple Heart was awarded posthumously, accompanied by these words from President Harry Truman: "Major Russell Vifquain Jr. stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live and grow and increase its blessings. Freedom lives and through it he lives in a way that humbles the understanding of most men."