Sgt. Maj. King (center) with crew in Vietnam.

AMES, Iowa – A former Iowa State University student from Muscatine who was MIA in 1968 during the Vietnam War will be honored by the university on Veterans Day.

Chief Master Sergeant Charles Douglas King was the son of Charles and Darlene King, Muscatine. In 1968, he went missing in action during a pararecsue mission in Laos. Ten years later, he was officially declared killed in action and awarded several medals. U.S. Bypass 61 in Muscatine was named for King in 2012. Buildings on several Air Force bases are also named for him. King was 22 at the time of his death.

King and four other former students who died in military service will be remembered during Iowa State’s Gold Star Hall Ceremony, 3:15 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 11, in the Memorial Union Great Hall. It is free and open to the public.

Former students are eligible for name placement in the Gold Star Hall — the war memorial in the university's Memorial Union — if they graduated from or attended Iowa State full time for one or more semesters, and died while in military service in a war zone. As names become known, they are added to the wall and the soldiers are remembered in the university's annual ceremony.

Iowa State has been able to memorialize King with help and materials from his sister, Sherry King of Muscatine.

A young life remembered

Charles Douglas King was born March 24, 1946, in Muscatine to Charles and Darlene King. He had an older sister, Esta, and two younger half-brothers. As a child, he loved spending time on his father's farm, hunting, fishing, and riding his bike and pony.

At Muscatine High School, he discovered a great passion for wrestling and being part of a team. He was popular and successful. A teacher once said that King gave him hope for his generation.

King also enjoyed activities that were dangerous. During high school, he worked for a silo company building grain bins, where he loved to climb to the top. He started parachuting and riding motorcycles as hobbies.

Following graduation in 1964, King enrolled at Iowa State as a forestry major. He joined Sigma Chi fraternity and enjoyed college life.

A pararescueman with a maroon beret

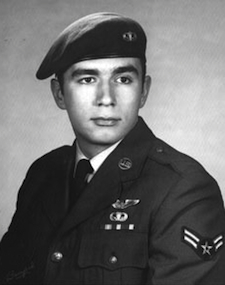

In 1966, at the age of 20, King was drafted into the U.S. Air Force. Following basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, he was selected for special training as a pararescueman. The mission of a pararescueman is to recover downed and injured aircrew members in austere and nonpermissive environments. This required rigorous training, and King earned a maroon beret, becoming the Air Force equivalent of a Navy SEAL.

According to the Pararescue Creed, "It is my duty as a pararescueman to save life and to aid the injured. I will be prepared at all times to perform my assigned duties quickly and efficiently, placing these duties before personal desires and comforts. These things I do “that others may live.”

Following graduation from jump school and special warfare training, King was assigned to the 40th Air Rescue and Recovery Squadron, stationed at the Nakhon Penom Air Base in Thailand. He was a part of the 40th Air Rescue and Recovery squad. By his final mission, King had completed more than 75 missions. According to military regulations, he wasn’t required to do more, and had orders in hand to return to the U.S.

King's final mission

The afternoon of Christmas Eve 1968, an Air Force pilot went down in neighboring Laos. The F-105 had been shot down between Ban Phaphilang and the Ban Kariai Pass. Its pilot, Maj. Charles R. Brownlee, successfully ejected, and his parachute drifted into enemy territory.

These enemy troops were known to aggressively pursue downed pilots and contest search and rescue efforts. Two helicopters immediately proceeded to the parachute's location in the trees. Numerous attempts were made to contact Brownlee on his survival radio until dark. Without radio contact or a night combat rescue capability, the rescue helicopters were ordered to return to the base.

At sunrise of Christmas Day, a search and rescue was organized. The crewmembers of Jolly 17 all volunteered: aircraft commander Lt. Col. William Cameron, co-pilot Capt. Robert Heron, flight engineer Sgt. Jerome Casey, and pararescueman A1C Doug King.

As the helicopter came over the parachute, Casey saw a man hanging by his harness, only a couple of feet off the ground. He was not moving. Suspecting an ambush, the rescue crew hovered out of range of ground fire and above the pilot while smaller aircraft flew over, trying to attract fire. The enemy did not respond and the trap was set.

King volunteered to descend to rescue the downed pilot. The commander realized it was the only way to rescue Brownlee, and lowered King and a stretcher to the ground. Just as he reached the ground, enemy troops began firing, first at the helicopter then at the men on the ground. King freed Brownlee and secured him to the stretcher. He signaled Casey to reel them up.

Only a few feet off the ground, King called on the radio, “I’m hit, I’m hit, pull up, pull up.” Normally, men would be hoisted clear of the trees prior to the rescue helicopter resuming forward flight, but enemy troops were hosing the helicopter with effective small arms fire.

If the helicopter stayed in the hover until the men cleared the treetops, it would certainly be shot down, crashing on Brownlee and King. Cameron elected to ascend straight up. He hoped this maneuver would lift the two men clear of the trees before instituting forward flight. As the helicopter moved up, the hoist cable caught on a tree and snapped, dropping King and Brownlee about 10 feet to the ground. Badly injured from the fall and wounded by enemy small arms fire, King made one last radio call, “Jolly, get out of here, they’re almost on top of me.”

The seriously damaged helicopter had to leave in order to save the lives of the other men. As it pulled away, enemy troops swarmed Brownlee and King; the helicopter was unable to fire at the enemy at the risk of hitting their own men. After two days of searching and numerous radio calls, King was officially declared MIA. He was promoted to Chief Master Sergeant.

Hope and honors

The family hoped for years that he would be found. But on May 15, 1978, Chief Master Sergeant Charles Douglas King was officially declared killed in action. He was awarded the Air Force Cross, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal, and the Purple Heart.

In February 1986, a Laotian refugee in the U.S. reported that he witnessed King’s capture, and observed them being taken away in a truck. In 1993, U.S. officials found an identification card with Charles Douglas King’s name, service number, date of birth and writing in Vietnamese that indicated that he was killed on Dec. 25, 1968.

King was also honored on June 12, 1979, for his professional dedication, courage and valor by the Air Force when it named a dormitory for him — King Manor at Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C. At Scott Air Force Base near Belleville, Ill., First Street was renamed King Street in his honor on June 28, 1979. On Feb. 27, 1990, another dormitory — King Manor at March Air Force Base in California — was named in his honor. And on Nov. 15, 1996, at Hickham Air Force Base in Hawaii, Building 1856 was dedicated to his memory. Most recently, on October 20, 2012, U.S. Bypass 61 in Muscatine was officially renamed “Douglas King Memorial Expressway.”

King is memorialized in Hawaii at Honolulu Memorial Cemetery with others who are MIA, lost, or buried at sea in the Pacific during World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Their remains have never been recovered, but their sacrifices have not been forgotten.