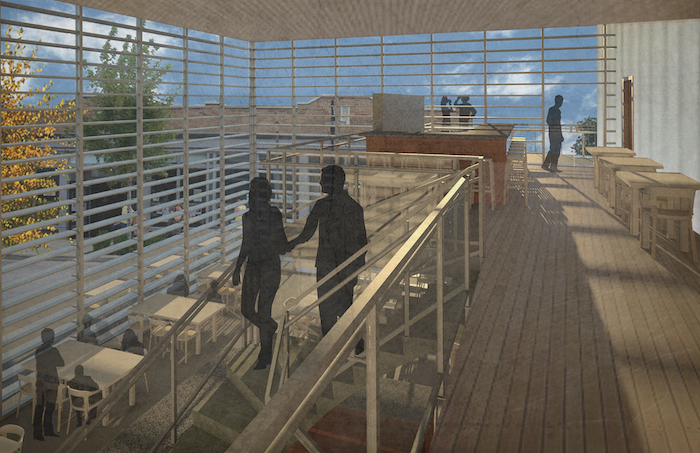

"Old North Bikes: Human Powered Revitalization in Old North St. Louis" by Stephen Danielson and Benjamin Kruse.

AMES, Iowa — Iowa State University architecture graduate students are among the winners of a national American Institute of Architects' student competition. More than 400 students from 38 schools participated in the competition.

Projects by three ISU teams were selected in the inaugural AIA COTE Top 10 for Students competition sponsored by the American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment (AIA COTE), Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) and ViewGlass.

The top 10 projects were displayed May 14-16 at the 2015 AIA National Convention in Atlanta and will be displayed again at the 104th ACSA Annual Meeting in Seattle in March 2016.

In announcing the winners, AIA COTE said, “The competition recognizes 10 exceptional studio projects that seamlessly integrate innovative, regenerative strategies within their broader design concepts. The program challenged students to submit projects that use a thoroughly integrated approach to architecture, natural systems and technology to provide architectural solutions that protect and enhance the environment.”

Selected teams from Iowa State include:

- Stephen Danielson, St. Joseph, Minnesota, and Benjamin Kruse, Philadelphia, for “Old North Bikes: Human Powered Revitalization in Old North St. Louis”

- Brandon Fettes, George, and Kyle Vansice, Des Moines, for “[Re] Sustaining Old North St. Louis”

- Heidi Reburn, New Albin, and Sean Wittmeyer, Fort Collins, Colorado, for “HRR: Harvest, Recycle, Reuse”

Sustainable building design

The Iowa State teams’ projects were developed in the fall 2014 Sustainable Building Design (Net Zero Design) graduate studio taught by associate professor Ulrike Passe and lecturer Kris Nelson. Students explored the relationship between buildings and environmental forces to produce design projects that make efficient use of energy, water, material and other resources, with the goal of achieving a sustainable and net zero energy building design (one that consumes roughly the same amount of energy as it produces).

“They were required to calculate annual energy consumption and design a building efficient enough that incorporating on-site renewables like active and passive solar would produce the necessary amount of energy over the course of one year,” Passe said.

The class addressed a site in Old North St. Louis (ONSL), an original streetcar suburb of St. Louis that is now part of the city proper and after years of deterioration is undergoing major redevelopment, restoration and rehabilitation.

“We always seek regional project sites that have a strong urban component so students must respond to other parameters in addition to sun and wind and include the community context,” Passe said. “This year they also had to react to one another’s projects all along one street corridor.”

Thirteen pairs of architecture graduate students collaborated with the Old North St. Louis Restoration Group, an active nonprofit community organization that buys and renovates properties to attract new businesses, residents and investment. The class visited the community last September and developed projects the rest of the semester.

“ONSL has already created a small center a few blocks south of North 14th Street and St. Louis Avenue with a farmers’ market, a community garden and artisan shops, but there are pockets of residential development scattered among vacant properties. Students proposed projects that would help tie together all the dispersed parts of the neighborhood, both commercial and residential,” Passe said.

While the project with ONSL was established prior to the AIA COTE Top 10 for Students competition announcement, it was almost tailor made for the contest requirements, Passe said.

“Most of the 10 sustainability measures used to evaluate the entries—including regional/community design, land use and site ecology, bioclimatic design, light and air, water cycle, energy flows, materials and construction and long life—were considerations already built into our course syllabus. It was especially beneficial that our project had such a strong community focus.”

At the end of the studio, Passe and Nelson encouraged students to submit their projects to the competition as a “good exercise to communicate their work to a broader audience.” Of the 13 teams, seven entered the contest and three placed in the top 10.

Old North Bikes

Danielson and Kruse chose a prominent corner at the intersection of two main roads for their mixed-use project, which featured a bicycle shop and “learn to earn” workshop (where young people could obtain a free bicycle by building one themselves) with four residential apartments above the retail space and a bike-servicing plaza and test track on the south side of the building.

The building incorporated roof-mounted photovoltaic panels, a small section of green roof and a sawtooth roof configuration over the workshop area to provide natural lighting. It also featured operable windows in the apartment units for natural ventilation and workshop doors that could rotate in place both for ventilation and to open the space to the street to encourage public interaction.

Key to the students’ design were louvered bamboo screens on each façade, which served multiple functions of providing privacy, sun shading, rain shielding and a visual “lightening” of the concrete structure.

“We saw sustainability as going beyond the building and the environment. The bike program promotes a healthy lifestyle and provides opportunities for social interaction and community connection,” Danielson said.

[Re] Sustaining Old North St. Louis

Fettes and Vansice proposed a modular, mixed-use design with a grocery store and café on the first floor and apartments on the second and third floors. Their project featured roof-mounted photovoltaics, a green roof for rainwater collection (to be stored and used in drip irrigation for the adjacent community garden) and automatically operated roof monitors for ventilation. The building incorporated clerestory windows in each apartment and the café to provide ample daylight without extreme temperature changes, an awning in front of the building and an operable shading device in the café. The project also included greywater recycling, solar hot water and radiant conditioning (both heating and cooling).

"[Re] Sustaining Old North St. Louis" by Brandon Fettes and Kyle Vansice.

One of the most innovative aspects was the use of cross-laminated timber as the primary structural material, Vansice said. This meant the majority of the components would be prefabricated and elements such as radiant ceiling and floor panels would be preassembled into the cross-laminated timber members, which would then be assembled on site.

“In assessing sustainability, we started focusing on processes around architecture and construction and how they fit into broader issues of climate change,” said Vansice, who received his bachelor of science in construction engineering from Iowa State in 2012.

In their contest submission, the students noted, “[Cross-laminated timber] drastically reduces the carbon footprint of the construction process as well as its impact to the neighborhood.” In addition, “the primary structural elements have been designed to make their reuse compatible in other projects in the future.”

HRR: Harvest, Recycle, Reuse

Reburn and Wittmeyer took a different approach, introducing a narrative of three Old North St. Louis residents as they spent a day interacting in the proposed building, which featured apartment units above a craft bakery and a two-story restaurant/bar.

“We showed the way people would experience the building at different times of day and how it would perform over time,” said Wittmeyer, who is pursuing double master’s degrees in architecture and urban design.

The narrative from 6 to 11 p.m., for example, followed “Jim” and “Alyson” through an evening meal at the restaurant followed by drinks at the bar. The competition presentation boards listed time of day, outdoor temperature and weather conditions, indoor activities, and amount of energy produced and consumed.

"HRR: Harvest, Recycle, Reuse" by Heidi Reburn and Sean Wittmeyer

The project incorporated strategies and systems customized for the St. Louis climate to maintain occupant comfort throughout the year, including a trombe wall, operable windows, a brise soleil and sun shading system, cross ventilation and reuse of heat generated in the restaurant kitchen and bakery. Photovoltaic panels, a roof garden and stormwater collection and storage also were a part of the proposal. Partition walls could be reconfigured to transform residences to offices and back again to provide a flexible space over the long term.

Innovations included combined uses for the brise soleil, which served both as a sunlight deflector and as a solar energy collector with integrated photovoltaic panels, and for the trombe wall, a passive solar wall collector that also pulled hot air from the building with stack ventilation. The students also proposed the use of fuel cells to store energy from renewable sources to power the bakery oven.

“We learned the importance of thinking about these different technologies, materials and strategies early in the design process,” Wittmeyer said. “A small decision or design change in the beginning can revolutionize how a space operates."