AMES, Iowa – Keith Vorst is trying to convince the world there’s value in something much of humanity considers utterly disposable.

Human beings discard hundreds of millions of tons of plastic every year, and much of it ends up in landfills where it may take centuries to decompose. Or, worse, plastics find their way into rivers and streams and eventually into the Earth’s oceans, accumulating into giant garbage patches. Only a fraction of all that plastic gets recycled.

But Vorst, an associate professor of food science and human nutrition at Iowa State University, insists there’s a better way. Vorst leads the Polymer and Food Protection Consortium at Iowa State, and he works with some of the world’s best-known corporations to find new uses for recycled plastics that both add value to products and save money.

“We want to take junk out of landfills and turn it into a valuable resource,” Vorst said. “We’re creating technologies that will have companies mining landfills and the oceans for plastic.”

Value-added plastics

So how would containers made from recycled plastics add value to their contents?

Vorst points to shelf life for food products as one of the most promising applications. Sausages and steaks, for example, change appearance in response to exposure to light when they sit inside grocery store coolers. Vorst and his colleagues have developed plastic containers that filter out some wavelengths of light and slow that aging process. The experiments took place in a lab in the Food Science Building, where Vorst and his team have access to a bank of commercial-scale coolers, just like those in grocery stores. Vorst said the results of the research have shown the experimental plastic materials can double the shelf life of some products.

But Vorst said recycled plastics may unlock value in a range of other ways as well.

“We’re currently looking at whether packaging can retain nutrients better when food is in the store,” he said. “That means the packaging could actually make the food more healthful than it would be otherwise.”

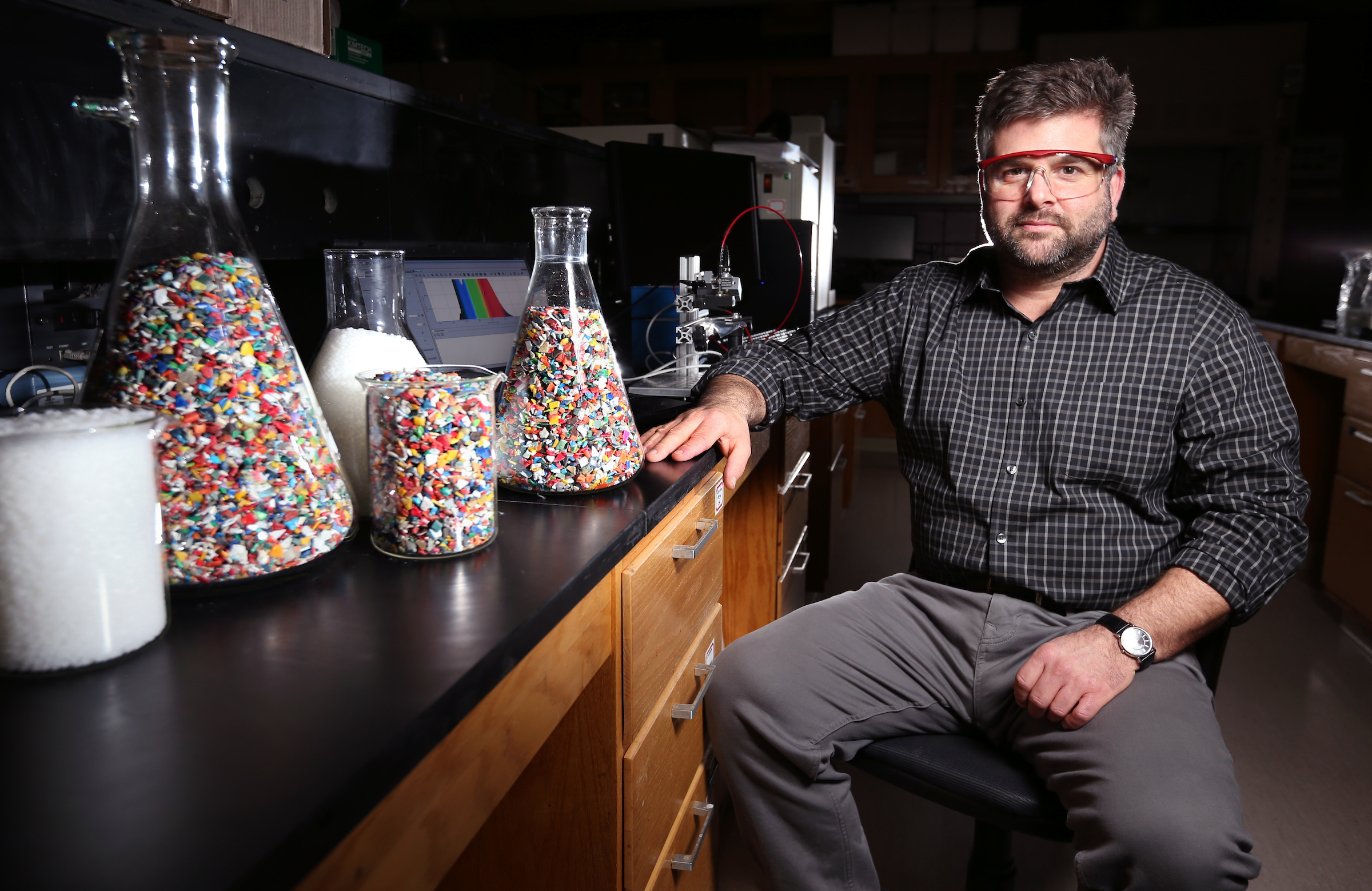

Keith Vorst with bits of recycled plastic bottles inside one of his laboratories in the Food Sciences Building at Iowa State. Vorst leads the Polymer and Food Protection Consortium and works with some of the world’s best-known companies to find new uses for recycled plastics. Photo by Christopher Gannon. Larger image.

Background

Vorst studied food manufacturing at Purdue before entering the private sector, where he worked for food packager Conagra in California. He discovered what he saw as a vast untapped potential for recycled plastics and went to Michigan State for a Ph.D. He later joined the faculty at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obsipo, California. He worked at Cal Poly for 10 years before joining Iowa State in 2014 and becoming director of the Polymer and Food Protection Consortium.

The consortium works with some of the world’s most recognizable companies – from Whole Foods to Taylor Fresh Foods to Johnsonville to the American Pop Corn Company – to develop and implement packaging innovations. Many of those innovations focus on the use of recycled plastics.

Vorst said recycled plastics often appear dull or discolored compared to virgin products. The recycling process also requires time and money that imposes additional barriers for many companies. But the European Union and states like California have implemented new regulations requiring minimum amounts of recycled materials to be utilized in the production of plastics, and some companies are looking for new technologies that will help them comply with such regulations. The consortium gathers copious amounts of data on plastic products from around the globe and works with companies to find solutions that make recycled products more attractive, Vorst said.

Reinventing the plastics wheel

Vorst said a new technology being validated by the consortium will allow manufacturers to track data continuously on plastics as they’re extruded by machinery. The technology monitors the extruder for organic and inorganic markers, as well as chemical and metal content of the plastic. Vorst said the technology will allow manufacturers to meet environmental standards with greater ease and precision.

Vorst said the consortium’s research could lead to new uses for recycled plastics not only in the food and beverage arena, but in industries as disparate as automotive parts and even clothing materials.

“We’re working toward a future where every pound of plastic is a sustainable resource and every piece of plastic has a home, and that’s not in a landfill,” he said.