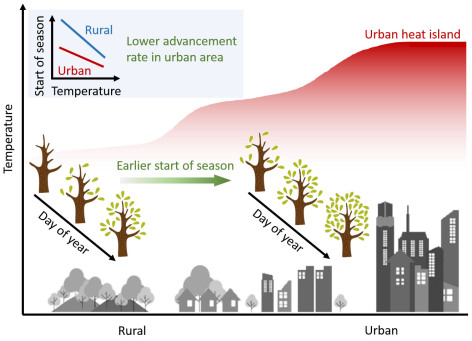

AMES, Iowa – A study of satellite images of dozens of U.S. cities shows trees and vegetation in urban areas turn green earlier but are less sensitive to temperature change than vegetation in surrounding rural regions.

It’s a symptom of the way cities trap heat, a phenomenon known as the “heat island effect,” said the authors of a recently published study in the academic journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study has ramifications for anyone interested in the ecological impact of climate change or who suffers from allergies, said Yuyu Zhou, an associate professor of geological and atmospheric sciences at Iowa State University and a co-author of the study.

The study examined satellite images of 85 large cities in the United States from 2001 to 2014. The satellite images allowed the researchers to detect the changes in greenness of plants and thus determine the timing when plants start to grow in spring. The data show the start of the season arrived on average six days earlier in the studied cities than surrounding rural areas due to the heat island effect.

Zhou said little research has investigated the connection between the heat island effect and phenology, or the study of cyclical and seasonal natural phenomena. Zhou said this kind of information will become increasingly important as scientists attempt to predict how plants will respond to changing environmental conditions, including climate change and urbanization.

“In the future, we want to have more accuracy in our earth system models to predict changes in our environment. Taking into account the interactions between temperature and phenological change in vegetation will mean those model predictions will improve,” Zhou said.

Lin Meng, an ISU Ph.D. student in geological and atmospheric sciences and lead author of the paper, said the study offers some insight into how a warming climate could affect vegetation in all kinds of environments, not just urban ones.

“We used the urban landscapes as a warming laboratory,” Meng said. “Using a space-time substitution approach, cities represent future warming scenarios.”

In addition to studying the urban-rural difference of the start of the spring season, the researchers analyzed the advancement rate of the start of season under warming. The study found the advancement of start of season of urban plants is lower than that of rural plants with the same amount of temperature increase, suggesting urban plants become less sensitive to temperature due to the heat island effect.

Meng said that might be due to warmer winters in urban areas. Some studies have suggested that trees need to be chilled enough in winter in order to be responsive to increases in temperature in spring. The elevated winter temperature in cities reduces the chilling accumulation and causes decreased sensitivity of phenology in urban areas. Zhou and Meng said there are ongoing discussions on the reason for the reduced advancement rate, and further studies must delve deeper into this question, but their data support that claim.

“Temperature is only one factor for the timing of vegetation growth, but it’s clearly an important one,” Zhou said.