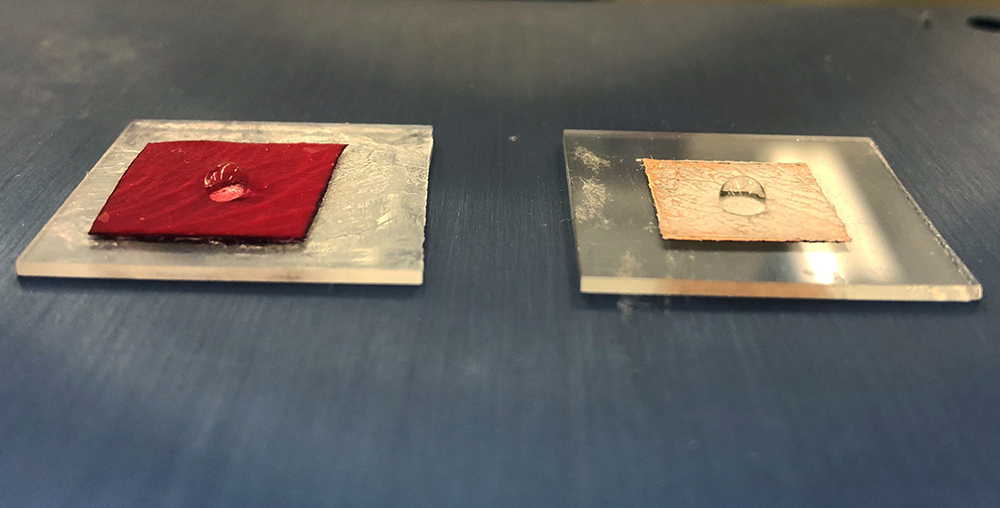

This lab demonstration shows how a rose petal and a metallic replica of the petal's surface texture repel water. The replica was created using the "frugal science/innovation" of Martin Thuo and his research group. Larger photo. Photo courtesy of Martin Thuo and his research group.

AMES, Iowa – Nature has worked for eons to perfect surface textures that protect, hide and otherwise help all kinds of creatures survive.

There’s the shiny, light-scattering texture of blue morpho butterfly wings, the rough, drag-reducing texture of shark skin and the sticky, yet water-repelling texture of rose petals.

But how to use those natural textures and properties in the engineered world? Could the water-repelling, ultrahydrophobic texture of a lotus plant somehow be applied to an aircraft wing as an anti-icing device? Previous attempts have involved molding polymers and other soft materials, or etching patterns on hard materials that lacked accuracy and relied on expensive equipment. But what about making inexpensive, molded metallic biostructures?

Iowa State University’s Martin Thuo and the students in his research group have found a way in their pursuit of “frugal science/innovation,” what he describes as “the ability to minimize cost and complexity while providing efficient solutions to better the human conditions.”

For this project, they’re taking their previous development of liquid metal particles and using them to make perfectly molded metallic versions of natural surfaces, including a rose petal. They can do it without heat or pressure, and without damaging a petal.

They describe the technology they’re calling BIOMAP in a paper recently published online by Angewandte Chemie, a journal of the German Chemical Society. Thuo, an associate professor of materials science and engineering with a courtesy appointment in electrical and computer engineering, is the corresponding author. Co-authors are all Iowa State students in materials science and engineering: Julia Chang, Andrew Martin and Chuanshen Du, doctoral students; and Alana Pauls, an undergraduate.

Iowa State supported the project with intellectual property royalties generated by Thuo.

“This project comes from an observation that nature has a lot of beautiful things it does,” Thuo said. “The lotus plant, for example, lives in water but doesn’t get wet. We like those structures, but we’ve only been able to mimic them with soft materials, we wanted to use metal.”

Key to the technology are microscale particles of undercooled liquid metal, originally developed for heat-free soldering. The particles are created when tiny droplets of metal (in this case Field’s metal, an alloy of bismuth, indium and tin), are exposed to oxygen and coated with an oxidation layer, trapping the metal inside in a liquid state, even at room temperature.

The BIOMAP process uses particles of varying sizes, all of them just a few millionths of a meter in diameter. The particles are applied to a surface, covering it and form-fitting all the crevices, gaps and patterns through the autonomous processes of self-filtration, capillary pressure and evaporation.

A chemical trigger joins and solidifies the particles to each other and not to the surface. That allows solid metallic replicas to be lifted off, creating a negative relief of the surface texture. Positive reliefs can be made by using the inverse replica to create a mold and then repeating the BIOMAP process.

“You lift it off, it looks exactly the same,” Thuo said, noting the engineers could identify different cultivars or roses through subtle differences in the metallic replicas of their textures.

Importantly, the replicas kept the physical properties of the surfaces, just like in elastomer-based soft lithography.

“The metal structure maintains those ultrahydrophobic properties – exactly like a lotus plant or a rose petal,” Thuo said. “Put a droplet of water on a metal rose petal, and the droplet sticks, but on a metal lotus leaf it just flows off.”

Those properties could be applied to airplane wings for better de-icing or to improve heat transfer in air conditioning systems, Thuo said.

That’s how a little frugal innovation “can mold the delicate structures of a rose petal into a solid metal structure,” Thuo said. “This is a method that we hope will lead to new approaches of making metallic surfaces that are hydrophobic based on the structure and not the coatings on the metal.”