We built a fake metropolis to show how extreme cold could wreck cities

As the world grows hotter, the whims of weather occasionally sucker-punch a typically warm place with crippling cold.

The result can be catastrophic failure of basic pillars of the built environment, from power and water to transportation and even the roofs of homes.

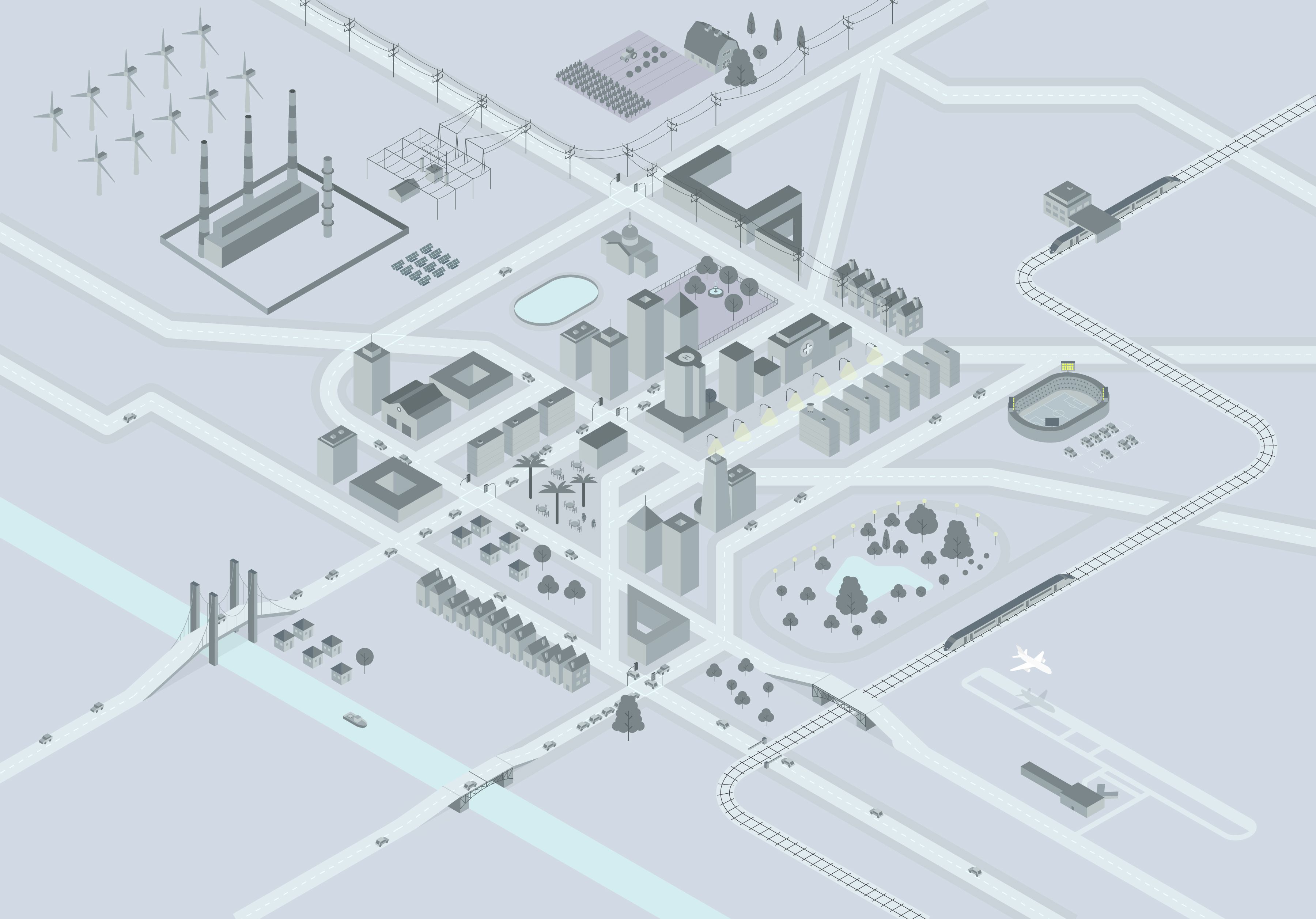

This project, the flip side of this story about unexpected heat, illustrates some of what can happen to a warm-weather place that is suddenly overwhelmed by an Arctic blast. Each of these breakdowns has happened somewhere, or in many places, around the world, but we’re putting them all in one fictitious town.

Welcome to Iceburgh! (Bring a coat.)

This is a place where residents sweat through summer so they can spend winter outdoors in T-shirts and shorts — exactly the opposite of Meltsville, its flannel-clad sister city to the north.

In Iceburgh, most heaters go unused, most restaurants feature patio bars.

However, at the moment, things far more critical than the margaritas are frozen.

Thanks to a wobble in the polar vortex, the temperature is frigid, and the town is slowly digging out of its first snowstorm in decades.

Transportation (mostly) stops

Iceburgh’s roads, rails and airways are a very cold, hot mess.

Cities far more accustomed to winter weather have been paralyzed by an inch of snow, such as the D.C. area. A deadly 2022 blizzard proved that even Buffalo could get more winter weather than it could handle.

In places that rarely experience snow and ice, even a coating can cause chaos — and Iceburgh has much more than a coating.

Roads and sidewalks are difficult to clear without an army of plows and snowblowers, and residents have already scooped up the meager supply of ice melt from hardware stores. The nearby hospital that excels at treating heat illness is prepping for cases of frostbite and the possible cardiac consequences of shoveling snow.

Visibility during the storm was low, and many vehicles became stuck or wrecked by drivers unfamiliar with navigating winter weather. Broken pipes are turning streets into ice rinks. Some side streets are blocked by trees that fell under the weight of snow and ice.

Bridges, which ice up before roads when cold air surrounds them, can become unstable if brittle parts contract too much or break, especially if winds are strong.

Road surfaces crack and crumble as water seeps into small crevices, freezes and expands, causing axle-rattling cracks and potholes as vehicles roll over them.

In cold-weather places and regions that routinely experience wide temperature swings, asphalt is formulated to be more resilient, and concrete is mixed with microscopic air bubbles that allow space for water to expand when it freezes without causing cracks, said Halil Ceylan, director of Iowa State University’s Program for Sustainable Pavement Engineering and Research. Not so in places where ice is rare.

Ceylan said runways usually fare well in the cold because their surfaces are built to be much more durable. Planes are fine, too, as the temperature at cruising altitude is routinely far below zero.

But add in precipitation, and you have problems.

Ice on a plane throws off its aerodynamics and makes it unstable. Runways have to be clear for plane wheels to have the proper surface friction to take off and land safely.

Even if planes and runways are dry, ground crews may have trouble maneuvering around snow and ice in the busy gate areas to get planes loaded and ready to fly. (Ceylan’s team has created a pavement-warming system that is being tested in three areas, including at Des Moines International Airport.)

[Winter storms wreak havoc on flights. Here’s why.]

Solving those problems requires de-icing and snow removal equipment, things in short supply at Iceburgh Regional Airport.

Meanwhile, at the rail station, trains have been stopped — with engines running, so their batteries don’t die in the cold — while crews try to thaw frozen switches that are blocked by snow.

One train has already derailed, a predictable result when a train goes through a switch that isn’t completely closed, said Allan Zarembski, professor and director of the Railway Engineering and Safety Program at the University of Delaware.

Ice buildup on tracks makes it hard for trains to brake or muster the traction to climb hills. Even without precipitation, tracks that are too cold have a physics problem.

Rails are assembled based on the area’s typical temperature range, accounting for how much the steel will expand at the hot end of the range and contract at the cold end, Zarembski said. If the temperature drops below that range, rails can contract so much that they pull apart at joints or welds.

Railroads in wintry places deploy train-mounted ice scrapers, switch heaters (including some that make it look like fire has engulfed the tracks) and enormous jet snowblowers — basically jet engines on rail cars — that can blast tunnels through the snow.

But Iceburgh has none of those things. Most residents, stuck in their homes, have hunkered down and cranked the heat.

Which contributes to …

A failing power grid

Power plants aren’t built for extremes, said Matt Eckelman, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northeastern University. They operate best in the middle of the temperature range for which they were designed.

In unusual cold, mechanical parts such as valves and actuators can freeze in position or not respond as quickly as they should.

“It doesn’t take much,” Eckelman said. “It can be just a single coupling. Just any one break in the line can take out that generation capacity.”

Natural gas wells can freeze, or their pumps can stop working. Wind turbines can ice up. Solar panels get covered with snow.

Power plants in warm places can be especially vulnerable because many parts, including huge pipes, often are not enclosed in buildings. The open design is cheaper to build but leaves the plants exposed when cold air arrives.

Wintry weather also can mangle the network that brings power from plants to homes and buildings. Aboveground lines and poles can be taken out by tree limbs, high winds and sliding cars, and substations and transformers develop mechanical failures of their own.

When the grid struggles, officials may resort to rolling blackouts to keep it from collapsing.

A combination of all these things took down the grid in Texas in February 2021, when an estimated two-thirds of Texans lost power, more than 11 million had water service disrupted, and hundreds died.

[Climate change may have worsened deadly Texas cold wave, new study suggests]

In the worst cases, such as a total power outage, residents can be in danger of freezing or at risk of carbon monoxide poisoning if they try to, say, start a fire in a fireplace where the chimney is blocked or run a generator or gas grill indoors.

If Iceburgh’s beleaguered grid fails, help probably won’t come from outside the area. When a hurricane or tornado causes outages, crews often rush in from other states. But a polar vortex blankets huge areas at once, and repair workers are often needed closer to home.

Nervous Iceburgh officials plead with residents to pile on blankets and sweaters and turn down the heat to conserve power.

A bursting water system

Power outages can and do take down water treatment plants, but the bigger water worry for Iceburgh is its pipes.

Water mains and pipes in cold places are buried several feet deep so that they will be safe from hard freezes. But in typically toasty Iceburgh, they sit mere inches below the surface — well within reach of the bitter cold that could cause them to contract and leak or break, especially if the water inside them froze and expanded.

Pipes situated below concrete or asphalt freeze more easily than ones buried under an insulating layer of grass. Old cast-iron pipes, still in use in many cities, are especially brittle and prone to breaking. During the 2021 Texas freeze, Fort Worth alone had 707 water main breaks.

All those burst pipes don’t just flood streets with water and ice, each one also reduces water pressure throughout the system. The same thing happens when smaller residential pipes break, in addition to creating huge messes inside homes.

Water pipes that are closer to outside air — inside a building’s exterior walls, for instance, or in an uninsulated attic or a crawl space — are susceptible to freezing. During the December 2022 cold in Atlanta, so many pipes burst in homes and businesses that police had to tell residents to stop calling 911 about them. (The first step should be to shut off the house’s water supply valve.)

If water pressure goes too low, the risk of contamination rises, and boil-water orders often follow.

Porous buildings

Some of the Iceburghers shivering in their homes feel drafts they’d never noticed before and see icicles forming on their eaves. Some are alarmed by water on drywall and ceilings. A couple of roofs appear to sag. What is happening?

Buildings in warm places are not constructed to the exacting standards of airtightness required by code or demanded by homeowners in very cold areas, said Pat Huelman, coordinator of the Cold Climate Housing Program with the University of Minnesota Extension. They may have little insulation, poor air sealing around windows and doors, and other opportunities for air to penetrate exterior walls and ceilings. Very old windows may not provide much of a barrier to cold.

When warm, humid indoor air collides with frigid outdoor air or chilled surfaces, you get condensation, which can collect in attics and on walls and windows.

If too much heat escapes through the ceiling and into the attic, snow on the roof will melt. Some probably will drip off and freeze into icicles. But some may refreeze at the roof’s edge, forming an ice dam that traps water. If that water seeps under shingles, it can back up into the eaves of the house and run onto ceilings or down inside walls. As the weather warms again, mold may grow.

[How to prepare your home before a blizzard and Arctic air strikes]

Heavy snow accumulation can make a building unstable or cause a low-sloped roof to sag or collapse. Occasionally, roofs that were built for cold aren’t immune. In 2010, the air-supported, Teflon-coated fabric roof of what was then the Minnesota Vikings’ stadium gave way spectacularly under 17 inches of snow.

Even the foundation of a building can be damaged by ice, Huelman said. “Frost heave” occurs when water freezes and expands enough to lift a footing or concrete slab. The slab can break or resettle off-kilter.

As Iceburghers shine flashlights into their attics and crawl spaces to look for ice and water, some are startled to see eyes peering back at them.

Chilly critters

Some birds and animals, notably squirrels, bats, mice and raccoons, are experts at weaseling their way into buildings for the winter in all kinds of climates. Manatees often cozy up to coastal power plants, where discharge water is warm and conservation-minded people sometimes provide snacks.

But some creatures accustomed to year-round warmth may be caught by surprise with nowhere to go.

Pelicans in North Carolina get frostbitten pouches, sea turtles in South Padre Island require rescue, and fishing off the Texas coast has been (temporarily) forbidden because frigid fish are so easy to catch. In Miami, cold-stunned reptiles tumble from trees so often that the National Weather Service warns of “falling iguanas.”

Iceburgh is obviously a made-up place, and it’s tempting to think real-world people rarely need to worry about occasional cold blips in the steady climb toward a hotter planet. But a warming climate is a more chaotic one, and the built environment needs to be resilient enough to handle the blips.

“What we’re trying to plan for,” Eckelman said, “is just a more extreme and unpredictable future.”