AMES, Iowa -- In 1996, when Ingrid Lilligren was a junior faculty member in ISU's art and design department and Jill Euken worked as an Extension field specialist at the university's Armstrong Research Farm in Lewis, they collaborated on a project to create artwork for the farm's new Wallace Foundation Learning and Outreach Center. Little did they know that this "beginning of a beautiful friendship" would lead to a partnership between the Bioeconomy Institute and the College of Design nearly 15 years later.

Thanks to their friendship, the institute's new Biorenewables Research Laboratory (BRL) -- set for dedication on Friday, Sept. 17 -- will not only be home to some of the university's most innovative research, but also some of its most inventive artwork.

Euken is now deputy director of the Bioeconomy Institute, and Lilligren is professor and director of integrated studio arts. The two bonded when Lilligren was commissioned to create and install a ceramic mural for the learning center. Over the years, the friends exchanged phone calls and emails. In 2008, they reconnected at a university awards luncheon.

The science of building a collection

"When I walked up to Jill, she whispered, 'I have something I want to talk to you about,'" Lilligren said.

"When you're dealing with Jill, there's never a moment when you think, 'What have I gotten myself into?'," Lilligren said with a laugh. "There's always this whir of excitement because you know this will be fun."

Euken wanted to discuss artwork for the new biorenewables building, which would be built in two phases. It had been decided to purchase the public-building-funded artwork upon completion of the second phase. Until then, the walls of the BRL would be bare.

"And a building without art really isn't a building," Euken laughed.

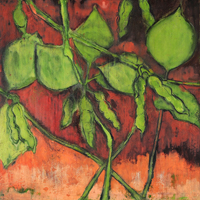

Encaustic paintings by

Associate Professor Barbara Walton use an innovative soywax

developed at ISU. Photo by Bob Elbert.

Encaustic paintings by

Associate Professor Barbara Walton use an innovative soywax

developed at ISU. Photo by Bob Elbert.

So the two discussed having design students and faculty create art on an ongoing basis. They formed a committee that included Barbara Walton, associate professor of art and design; Tonia McCarley, Center for Biorenewable Chemicals assistant director; and the Bioeconomy Institute's Diane Meyer, grants manager; Diane Love, administrative assistant; and MaryAnn Sherman, former communications and marketing coordinator.

"I've always been most comfortable having one leg in two different cultures and bridging them," Euken said. "And it just makes sense that when you find someone in a different department who also likes to mix it up, that you work together."

"We immediately decided to have a juried competition for students, then place their art in the building," Lilligren said.

Last spring, 22 integrated studio arts students produced work for the BRL's inaugural Sustainable Art Juried Competition. Students were asked to create art from or with images of natural materials. They also had to write statements about the lifecycle of the materials used or the lifecycle of the subject matter depicted.

Cash awards, ranging from $750 to $75, were provided for the top four place winners, by the institute's non-state funding. Winners were selected on Earth Day in April; Katie Palmer's reduction woodcut, "Corvidae Corvus," took Best in Show.

The art of being good neighbors

Meanwhile, Sherman and Euken asked Lilligren and Walton if they could make something with biochar. Biochar is a charcoal co-product of bio-oil made from cellulosic biomass. When applied to the soil, it can restore nutrients and sequester carbon.

Barbara Walton with her

biochar drawing, an underwater abstraction. Photo by Bob

Elbert.

Barbara Walton with her

biochar drawing, an underwater abstraction. Photo by Bob

Elbert.

Lilligren set in motion the "Charcoal Challenge" for studio arts faculty. The institute provided each artist with about a pint of red oak charcoal powder. Some rubbed the charcoal into paper, and then erased areas to create light and dark values. Walton added linseed oil to the gritty powder before drawing with it. And Lilligren fired some biochar onto a tile to make a glaze. The seven faculty pieces will be on temporary display in the Bioeconomy Institute's office suite.

Soywax-based encaustic paintings by Walton also will be exhibited. An ancient technique, encaustic painting involves adding colored pigments to heated wax and applying it to wood or canvas. It traditionally uses beeswax or petroleum-based wax.

Walton's

soywax and pigment on baltic birch panel, "Bean Number

10." Photo by Bob Elbert.

Walton's

soywax and pigment on baltic birch panel, "Bean Number

10." Photo by Bob Elbert.

However, Walton has worked with Toni Wang, professor of food science and human nutrition, to develop a safer, more affordable and environmentally friendly soy-based wax. The "green" wax is creating quite a lot of excitement in the encaustic painting art world, says Lilligren.

Other plans are being fleshed out to "solidify the good neighbor relationship" between the scientific institute and the designers and artists next door. Faculty who teach drawing or biological and pre-medical illustration will be encouraged to use the visual BRL laboratories and the ISU BioCentury Research Farm as settings for student drawing assignments.

"There haven't been any hurdles in accomplishing this. It just takes persistence," Lilligren said. "And working with Jill makes things frictionless. With her, nothing is ever, 'We can't do that,' but 'We can't do it that way, but we can do it this way.'"

Student artist Liza

Sidorowych's "Bountiful Butterfiles" on display

in the BRL lobby. Photo by Leah Hansen.

Student artist Liza

Sidorowych's "Bountiful Butterfiles" on display

in the BRL lobby. Photo by Leah Hansen.

JIll Euken with student

Chris Gordon's second-place-winning mixed-media piece as it

awaits proper installation. Photo by Leah Hansen.

JIll Euken with student

Chris Gordon's second-place-winning mixed-media piece as it

awaits proper installation. Photo by Leah Hansen.

Associate professor

Brenda Jones' self portrait made with biochar, awaiting

installation in the BRL. Photo by Leah Hansen.

Associate professor

Brenda Jones' self portrait made with biochar, awaiting

installation in the BRL. Photo by Leah Hansen.