AMES, Iowa -- Softball field ... butterfly garden ... yoga space ... greenhouse ... amphitheater. Sounds like a city park, right? Nope.

How about the grounds of Iowa's new women's prison?

At least that's the vision of some Iowa State University landscape architecture students, based on their research and discussions this spring with offenders and staff from the Iowa Correctional Institution for Women (ICIW) in Mitchellville. They've worked together for the past three months, thinking outside the box of typical prison landscape design to envision something truly unique. And everyone is pretty pumped about what they've come up with.

Wachtendorf

Wachtendorf

"We're blown away. This has completely exceeded my expectations," said Warden Patti Wachtendorf.

When the $68 million expansion and modernization of ICIW is completed in late 2013, the crowded, antiquated facility will offer state-of-the-art resources to encourage reform and assist those reentering society. And the plan calls for the landscape to contribute to the rehabilitative effects.

The first-ever collaboration between Iowa State and ICIW started last fall when the Department of Corrections contacted the university with the idea to engage students in the landscape design (designed by STV, New York, and Design Alliance, Waukee).

The request found its way to the ISU College of Design's landscape architecture program. Faculty created a seminar, "A Landscape Within: Design for Plants and Prison," to be taught in spring by Lecturer Julie Stevens. The class just wrapped up with presentations by the students and kudos from an enthusiastic warden.

Digging deep

Stevens

Stevens

Stevens said the prison project gave the upper-level students "a means to understand some of the deeper psychological issues associated with landscapes."

About 60 percent of the women offenders at ICIW have mental health issues; about that many need substance abuse treatment. More than half have been sexually abused.

"In the class, we've looked at how natural environments have rehabilitative effects," Stevens said. "Common prison landscapes are void of trees and nature, but we're trying to make a case that nature actually has a calming or positive effect that would be beneficial."

Students spent the early part of the semester reading first-person accounts by women prisoners, visiting the facility and expansion site and conducting focus groups. They also researched issues related to prison design, such as social and behavioral theory, therapeutic gardens, recidivism and surveillance. Throughout, they wrote reflections on their experience.

"At the beginning some were really nervous about meeting the inmates, and afterwards, they said, 'They're just people who are really excited about planting flowers and vegetables,'" Stevens said.

Butterflies and sight lines

Existing patio

Existing patio

As Wachtendorf told the students, the prison is home for these women.

"Although this is a prison, we told you that we didn't want it to look like a prison," Wachtendorf said. "And you listened. You listened to the officers and the offenders."

And when they listened during focus group sessions at ICIW, the students got an earful.

One offender talked about how important it was to look beyond the fence and see a distant farmstead. Another remembered the facility as a girls' school and didn't want that history lost.

They told the students they'd like a play area for their kids who visit -- something that doesn't look like a prison. We miss the old greenhouse, they said. Can we have seating areas for small groups so we can visit with friends? We like playing softball and watching plays. We want to see butterflies, birds, wildlife. And color. Lots of color.

The staff had plenty to share, too. Most of it was about security. They stressed the importance of clear sight lines, so their observation would not be blocked by dense plantings, foliage or landscape structures. They asked the students to forgo landscaping materials that could be made into weapons. And to avoid creating potential hiding places.

Despite the constraints, Stevens said, it was clear that Wachtendorf and her staff "were all committed to finding ways that will allow for an interesting and rehabilitative landscape."

It was up to the students to discover ways to do so.

Gardening, wholeness, tranquility

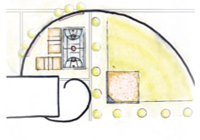

To develop designs for the 30-acre site (and handle the conflicting needs), students worked in three teams. One focused on reducing recidivism. They developed a network of integrated, functional spaces, using colorful trees and shrubs, textured paths, and partial brick-wall "ruins" as a reminder of the prison's past. They proposed a production garden, greenhouse and outdoor classroom where inmates could hone skills marketable in Iowa. And they included intimate seating areas, and therapeutic, butterfly, meditation and patio gardens.

In the second team's proposal, an iconic spiral form based on the Fibonacci mathematical sequence, commonly found in nature (nautilus, sunflower, for example), is used to unify the site and promote a sense of wholeness. It is meant to bring the inmates back to nature as it spirals to the center through five functional outdoor spaces -- home, therapy,recreation, spiritual and education.

The third team's proposal -- based largely on the offenders' desire for color -- focused on unified tranquility through color. They designed spaces and outdoor "rooms" that could benefit and improve the mental, physical and emotional well being of the offenders, staff and visitors. Different color palettes and patterns were used "to evoke, enhance or subdue" certain feelings, allowing for various experiences and moods. They included a therapeutic garden, semi-private areas, yoga space and a separate staff break area. The visitor area used wood and other "softer" materials, with trees and planters blocking visitors' view of the prison. The design included a place to gather in small groups; paths and spaces for personal reflection; a therapeutic garden outside of the hospital; softball diamond, volleyball court and game tables; and an outdoor classroom and informal study spaces.

On the right path

Tim Darr, ICIW captain and transition team leader, appreciated the students' "can-do attitude."

"They constantly looked for ways to make it all work. On their second visit, they returned with design changes to accommodate our security needs," Darr said. "It just floored me how well the students listened and grasped what we needed.

Darr

Darr

"It will be a win-win for the state if they can continue developing their designs," Darr added.

Wachtendorf invited the nine students to visit after they graduate ("We're always there!") and see how the project turns out.

"I like the passion that I see in all of you, and I appreciate that," she told the students.

"You did a fantastic job. And I will recommend to the director that we continue to work together," Wachtendorf said.

Stevens said plans are in the works to continue the collaboration. All the work -- the designs, research and reflections -- from this class will be included in a written report to the Corrections Department. The state awarded ISU a second grant of $25,000 to create a studio class. And some seminar students want to continue developing their ideas in independent study projects.