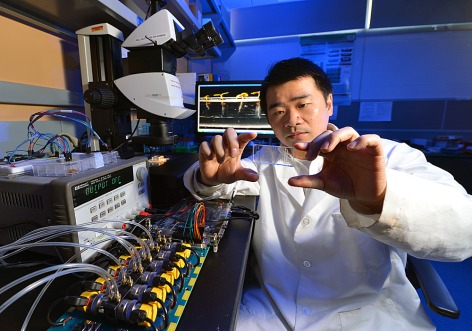

Iowa State's Liang Dong examines a microfluidic seed chip, an essential part of the instrument he's developing to study the effects of genes and environmental conditions on plant phenotypes -- the look, size, color and development of plants. Larger image. Photo by Bob Elbert.

AMES, Iowa – Let’s say plant scientists want to develop new lines of corn that will better tolerate long stretches of hot, dry weather.

How can they precisely assess the performance of those new plants in different environmental conditions? Field tests can provide some answers. Greenhouse tests can provide some more. But how can plant scientists get a true picture of a plant’s growth and traits under a wide variety of controlled environmental conditions?

That job has been too big and too precise for most laboratories. There are a few labs around the world that can do the work, but the studies are expensive, limited and require time and labor. There hasn’t been an accessible test instrument with enough scale, flexibility and resolution to produce all the data scientists need, said Liang Dong, an Iowa State University associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

That has Dong leading a research team that includes Namrata Vaswani, an Iowa State associate professor of electrical and computer engineering; Maneesha Aluru, formerly of Iowa State and now a senior research scientist at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta; three doctoral students and four undergraduates who are all working to build a high-tech solution for plant scientists. His idea is a greenhouse on a chip – an instrument that incorporates miniature greenhouses, microfluidic technologies that precisely control growing conditions and big data tools that help analyze plant information.

He calls his instrument a “transformative leap” in the study of plant phenotypes – the look, size, color, development and other observable traits of plants.

“The instrumentation will make breakthroughs toward solving grand-challenging, large-scale problems in the field of phenomics,” Dong said. “We are building resources to benefit plant biology researchers and hopefully the new instrumentation will create a paradigm shift in the plant phenomics area by placing powerful data analysis capability in the hands of researchers.”

The project started nearly two years ago with a $119,500 seed grant from Iowa State’s Plant Sciences Institute and is now supported by a three-year, $697,550 grant from the National Science Foundation.

The research project has already produced a technical paper, “Plant chip for high-throughput phenotyping of Arabidopsis,” published online and in the April 7 issue of the journal Lab on a Chip.

To date, Dong and his research team have been building the necessary components for a phenotyping instrument. Now they’re working to integrate the parts and pieces into a complete, flexible system that can handle a variety of research projects.

“We’re building a toolkit that people can assemble and use to meet their needs,” Dong said. “We originally thought this would look at seeds growing in a cube. But now this can be scaled-up, depending on the growth stage researchers want to study. If it’s a plant’s first 10 days, we can make parts of the instrument smaller. If it’s four weeks, we make them bigger.”

Here’s how the instrument will work:

Dong and his team will build miniature greenhouses that precisely control light intensity, humidity, temperature, carbon dioxide, chemicals and even pathogens. Plant scientists will fill the miniature greenhouses with clear, vertical and disposable chips containing seeds that will grow into seedlings.

Hundreds of the chips-in-mini-greenhouses can grow thousands of plants at the same time, each greenhouse providing different environmental conditions. Dong’s current goal is to get 128 of the growth chambers working simultaneously and independently.

As the plants within all those chambers grow, a camera attached to a robotic arm takes thousands of images of cells, seeds, roots and shoots. The images record traits such as leaf color, root development and shoot size, giving researchers clues to the relationship between a plant’s genotype, the growing conditions and the observable traits of its phenotype.

It will take big data tools to help researchers store, manage and analyze all the photo data collected by the instrument.

The new instrument’s capabilities are significant to researchers: “The system will largely facilitate plant phenotyping experiments that are impossible by current techniques,” Dong said.

He said he’s already using some components of the instrument to work with Iowa State agronomists Thomas Lubberstedt, who’s studying germination of pollen at different temperatures, and Madan Bhattacharyya, who’s studying how fungal pathogens interact with soybean seeds at different moisture levels.

As the toolkit develops, Dong said he hopes to move beyond plants and use it for studies of insects or even small fish.

One day, he hopes to have a commercial instrument that can be used by biological researchers around the world.

“I’m making small things here,” Dong said, “but hopefully they can make a big impact.”