Iowa State's James McCalley describes computer models showing the effects of tying the country's two major power grids together. Larger photo. Photo by Werner Slocum, NREL/DOE.

AMES, Iowa – The nearly 4,000 wind turbines all over the Iowa countryside, totaling more than 6,900 megawatts, provided almost 37 percent of all in-state electricity production in 2016. That’s enough to power about 1.8 million homes.

But, on cool, windy days, when production is high and local demand is low, the market for any excess production is limited to the central and eastern states. No matter if western states are heating up and demand for power is peaking.

That’s because the country has three primary power grids – the Eastern Interconnection, the Western Interconnection and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas – and very little electricity moves among them. The eastern and western grids are separated by a seam that generally runs north and south of the Nebraska-Wyoming border.

As part of a $220 million Grid Modernization Initiative announced in January 2016 by the U.S. Department of Energy, Iowa State University’s James McCalley is working with researchers from national laboratories and the utility industry to study ways to tie the big eastern and western grids together.

The two-year, $1.5 million project is led by Aaron Bloom of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory based in Golden, Colorado.

“In Iowa, about 35 percent of our electricity is renewable energy,” said McCalley, an Anson Marston Distinguished Professor in Engineering, the Jack London Chair in Power Systems Engineering in the department of electrical and computer engineering and an associate of the Energy Department's Ames Laboratory. “If we want the rest of the country to be at 35 percent renewable energy, this is what you want to do.”

Independent grids

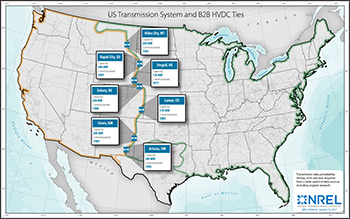

This map shows the country's three primary power grids -- the

Eastern Interconnection, the Western Interconnection and the

Electric Reliability Council of Texas -- and the seven small

connections between the eastern and western grids.

Larger image. NREL image.

McCalley said the three major parts of the country’s grid developed independently over time. Each now operates out of sync with the others. That makes it very difficult to send power across the seams using conventional high voltage alternating current (HVAC) transmission. The only alternative is to use high voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission with power converters at either terminal.

With most of the country’s demand for power on the coasts, there was never a strong economic motivation to build transmission capacity across the grids, McCalley said. But, with today’s production of wind energy in the prairie states and solar energy in the desert states, there’s now strong economic motivation to move power among the grids.

Seven small HVDC connections have been built in the U.S. between the eastern and western grids with an eighth in Alberta, Canada – the transmission is made possible by back-to-back stations that convert HVAC from one grid to HVDC that can cross the seam and then back to HVAC for the other grid.

McCalley called the connections “very small threads” – they can carry nearly 1.5 gigawatts, in comparison to the country’s installed generation capacity of more than 1,000 gigawatts.

“We can use these threads for the economic exchange of energy across the seams, but not for much of that, relative to potential,” McCalley said.

Models and models

McCalley and his Iowa State research team – postdoctoral research associates Ali Jahanbani (now of the University of Calgary in Canada) and Hussam Nosair; and graduate students Armando Figueroa and Abhinav Venkatraman – have built computer models simulating 15 years of grid improvements and operations to study the best ways to generate power and transmit it to and from the eastern and western grids.

They’ve looked at four designs, all with the idea of boosting the nation’s use of renewable electricity:

- Maintaining existing cross-seam capacity;

- Increasing the capacity of the current system of back-to-back conversion stations along the grid seam;

- Building major east-west transmission lines from the middle of one grid to the middle of the other, thus avoiding system bottlenecks close to the seam;

- And building a “macrogrid” of major transmission lines that loop around the West and Midwest, with branches filling in the middle and connecting to the Southeast. This design connects the West Coast to the Midwest, allowing more wind and solar energy to move across the grids. It spans time zones, allowing different regions to transmit power back and forth, helping each other meet daily demand peaks. It also allows regions to help each other meet annual demand peaks by sharing excess capacity, thus growing capacity without building additional power plants.

Additional studies by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington, are analyzing production costs and power flows.

The studies are new territory for the researchers.

“Nobody has studied interconnecting the Eastern and Western grids at this level before,” McCalley said. “It takes computer runs of six to eight hours to account for operation of and investment in both grids, spanning almost the entire nation over 15 years. And these runs must be repeated numerous times to address all four designs with various sensitivities on those designs.”

Those models indicate there are good reasons to connect and modernize the country’s biggest energy grids.

“There are two main drivers for benefits of cross-seams transmission,” McCalley said. “That’s wind energy moving from the middle of the U.S. to the coasts, and sharing of capacity between regions for reliability purposes.”

Contacts

James McCalley, Electrical and Computer Engineering, 515-294-4844, jdm@iastate.edu

Mike Krapfl, News Service, 515-294-4917, mkrapfl@iastate.edu

Quick look

With today’s production of wind energy in the prairie states and solar energy in the desert states, Iowa State University's James McCalley said there’s strong economic motivation to move power to and from the country's primary power grids. McCalley and his research team are working with researchers from national laboratories and the utility industry to study ways to tie the big eastern and western grids together.

Quote

“In Iowa, about 35 percent of our electricity is renewable energy. If we want the rest of the country to be at 35 percent renewable energy, this is what you want to do.”

James McCalley, an Anson Marston Distinguished Professor in Engineering

Research partners

In addition to Iowa State, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the seams study includes researchers from:

- Argonne National Laboratory

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- Midcontinent Independent System Operator

- Southwest Power Pool

- Western Area Power Administration

More grid studies

Two Iowa State University electrical engineers have won Department of Energy grants to help improve the country's power grid. One project will develop real-time monitoring and modeling of modern power grids, including renewable energy sources, for better system control and reliability. The other project will address the challenges of adding high levels of intermittent power sources to the grid, mainly wind and solar power.