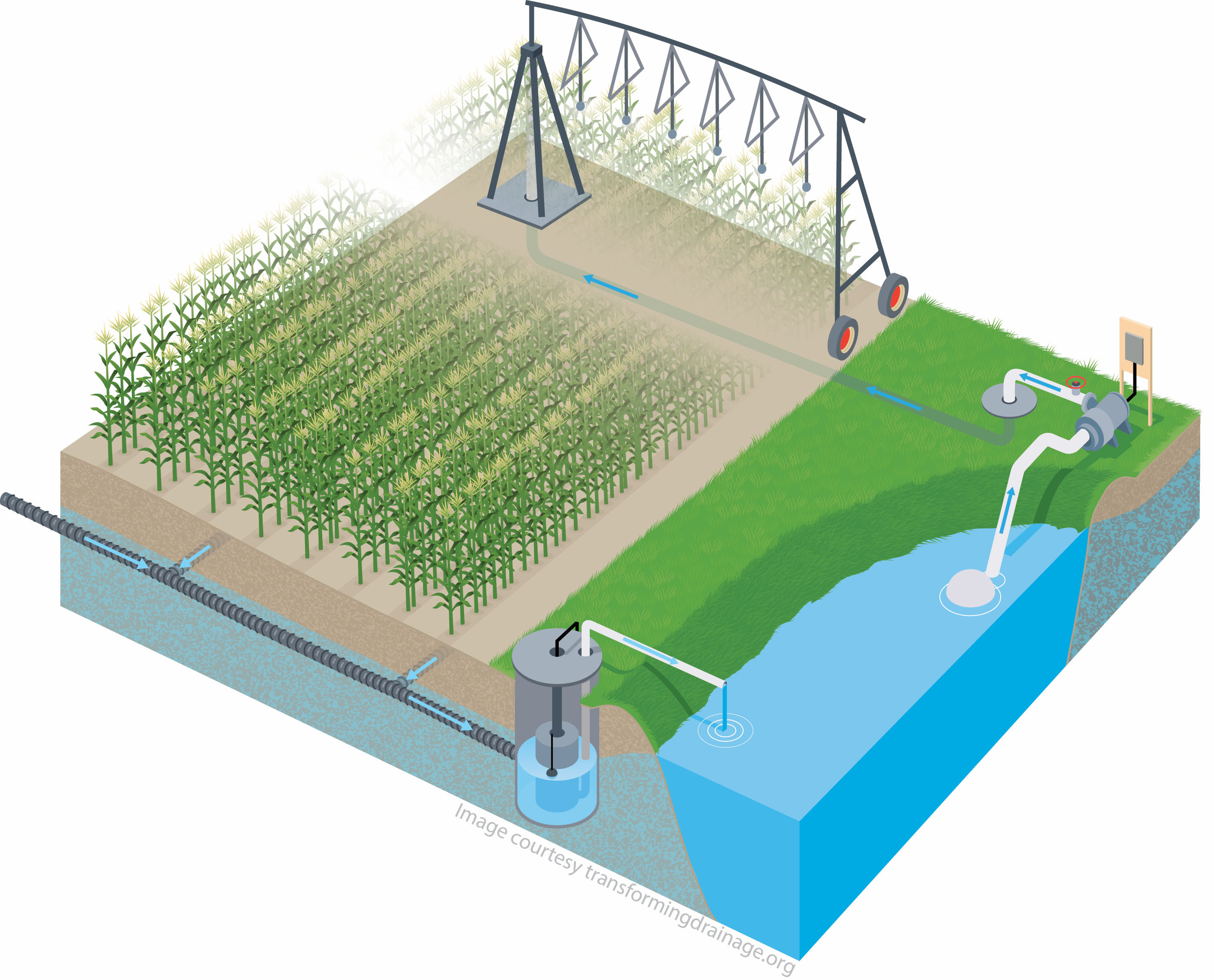

This illustration shows how a recycling system might look for drainage water from an agricultural field. The Iowa Nutrient Research Center has provided funding to study this concept and others to address water quality concerns. Image courtesy of TRANSFORMINGDRAINAGE.org and used with permission. Larger image.

AMES, Iowa – A research center at Iowa State University is seeking new proposals for water-quality projects, forging ahead with its mission to provide the scientific support necessary to address one of the state’s most pressing concerns.

The Iowa Nutrient Research Center began accepting proposals this week from scientists to address water-quality issues related to nutrient loss from farm fields and land use practices. The center, established in 2013, selects promising proposals every year and provides funding to get them underway.

Water quality has grown as a major concern among state leaders in recent years. Nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous leach out of agricultural land and eventually find their way into the Gulf of Mexico, where they contribute to a hypoxic zone that threatens habitat for plant and animal life. ISU personnel played a central role in establishing the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, a science-based framework to assess and reduce nutrients in Iowa waters.

The Iowa Nutrient Research Center seeks to fund scientific efforts that will help to meet the goals identified in the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy. Since its inception, the center has funded 60 projects, many of which address issues such as farm management practices and soil health, with a total of more than $7 million. The funding comes from state fees assessed on fertilizer sales and pesticide registrations, which amounts to roughly $1.5 million per year.

The center aims to spur research that develops a set of management tools that fit a wide range of variables, said Hongwei Xin, center director.

“There’s no one single practice that will fit each farm,” Xin said. “You have to develop a suite of practices and the research to go with that. To make informed decisions, you have to rely on science. That’s why we’re here.”

Each project must make use of expertise at Iowa State, the University of Iowa or the University of Northern Iowa, with some projects featuring collaboration across institutions. The research evaluates the effectiveness of current and emerging practices to improve water quality and slow nutrient loss from agricultural land.

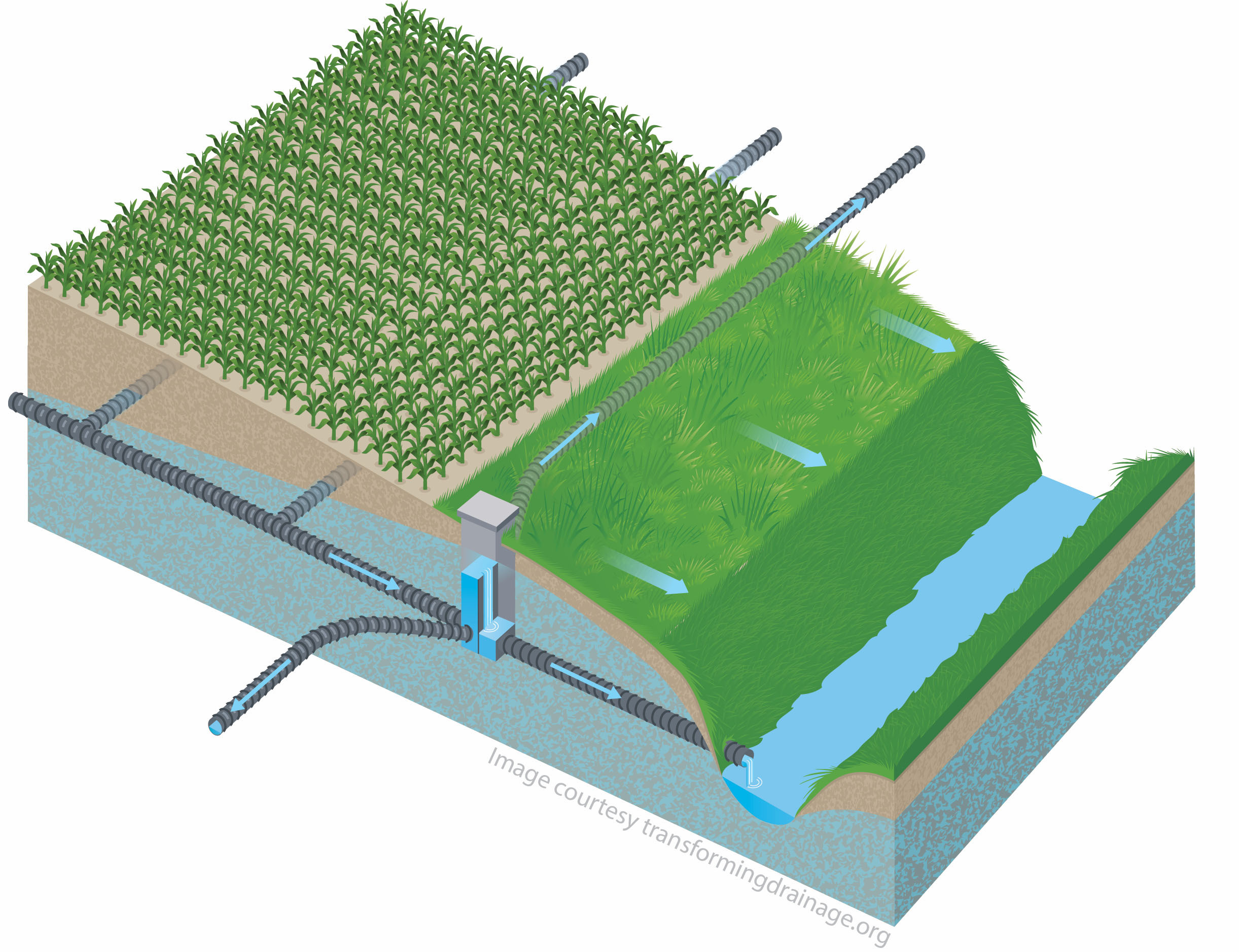

This illustration depicts a saturated buffer, which redirects drainage water along the sides of fields rather than directly into a stream. Image courtesy of TRANSFORMINGDRAINAGE.org and used with permission. Larger image.

Success stories

Previous research funded by the Iowa Nutrient Research Center has contributed to a growing set of tools to address Iowa’s water quality needs.

Michelle Soupir, an associate professor of agricultural and biosystems engineering, leads research on bioreactors, or areas on the edge of farm fields where tile-drainage water runs through bio-based materials such as wood chips to convert nitrates into gaseous nitrogen. The Iowa Nutrient Resarch Center funded a pilot project to test woodchip bioreactors on an ISU research farm, allowing scientists to test the concept under controlled conditions.

Soupir said there are at least 60 bioreactors installed on Iowa farm fields, and the results have shown promise. Soupir said performance of bioreactors varies across individual sites, but studies have shown they reduce the nitrate level of water passing through them by an average of about 43 percent.

The center also has provided funding to begin research on drainage water recycling, a new concept with potential to reduce the amount of water leaving agricultural fields. Matt Helmers, a professor of agricultural and biosystems engineering, said water recycling involves the installation of a reservoir on a farm where field drainage is routed and stored. This captured water would then supply an irrigation system that applies the water back onto the field at a time of a farmer’s choosing.

Helmers said the research is still in its infancy, and questions such as crop yield impacts, the best way to capture the water, costs, benefits and the hydrologic impacts of the system remain unanswered. The promise of recycling drainage water lies in its ability to reduce the sheer amount of water flow from fields and to allow farmers to use the captured water strategically, perhaps through traditional overhead irrigation systems or some other method. That could lead to improved crop performance and a better bottom line, Helmers said.

Saturated buffers intercept tile drainage water from fields near the edge of the field and redistribute the water back into streamside soils, rather than letting it run directly into a stream. The water moves through soil, triggering a biological process that can transform 50 to 70 percent of the nitrate in the drainage to nitrogen gas. Tom Isenhart, a professor of natural resource ecology and management, said there are saturated buffers at 12 sites in north-central Iowa where researchers are monitoring their performance, and he said the practice is poised to expand in the next few years.

Momentum is building among a range of stakeholders to find new strategies to safeguard Iowa’s water quality and to stop nutrients from agricultural fields from running downstream, said Malcolm Robertson, a program coordinator with the Iowa Nutrient Research Center.

“There’s definitely momentum and concern for water quality,” Robertson said. “I think everyone involved – from the producers to the researchers to the agriculture associations – wants to find the best way forward.”