Skyscraper Central: Why Are So Many of Chicago’s Tallest Buildings Located Downtown?

By The Curious City team

Skyscraper Central: Why Are So Many of Chicago’s Tallest Buildings Located Downtown?

By The Curious City teamIf you fly into Chicago, it’s hard to miss that recognizable cluster of skyscrapers that rise up from downtown, creating the skyline that is often depicted on postcards and other souvenirs.

There are some pretty tall buildings in other Chicago neighborhoods, but buildings that are 60 stories or taller are all in the Loop, or in the neighborhoods adjacent to downtown. This phenomenon led Keonte Brooks to send this question to Curious City:

Why are all the really tall buildings downtown but nowhere else throughout the city?

For the answer, we turned to two experts: Thomas Leslie, a professor of architecture at Iowa State University, and Jen Masengarb, former director of interpretation and research at the Chicago Architecture Foundation and currently the senior project manager at the Danish Architecture Center in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Both weighed in on what makes the Loop the destination for Chicago’s tallest buildings, why the earliest skyscrapers were built there in the first place, and whether we might expect any changes to the city’s skyline anytime soon.

Below are some highlights from this interview, which has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Why do cities, like Chicago, often have a cluster of skyscrapers in one area?

Masengarb: Cass Gilbert, a late 19th and early 20th century architect, said a skyscraper is “a machine designed to make the land pay.” So if you’ve paid for a plot of land and it’s expensive, you want to do everything you can to get the biggest return back on that investment. So you can put up a building with just one floor of tenants and rent out that space. But what if you put up two floors of tenants and stack them on top of each other? Then you can earn twice as much, or maybe one and three quarters the amount of money.

And so the idea is that each floor of that tall building is hoping to make money for that single plot of land right there. The higher you build, the more tenants you have, and the more tenants you have, the more revenue you’re going to get.

Leslie: Traditionally, you see skyscrapers getting built where land prices are the highest. It costs a lot of money to build tall, and therefore when you have land values that are very expensive, it’s easy to make enough money to overcome the cost of going high. Land values tend to be expensive in one central district, and that’s in general why skyscrapers at least start to cluster.

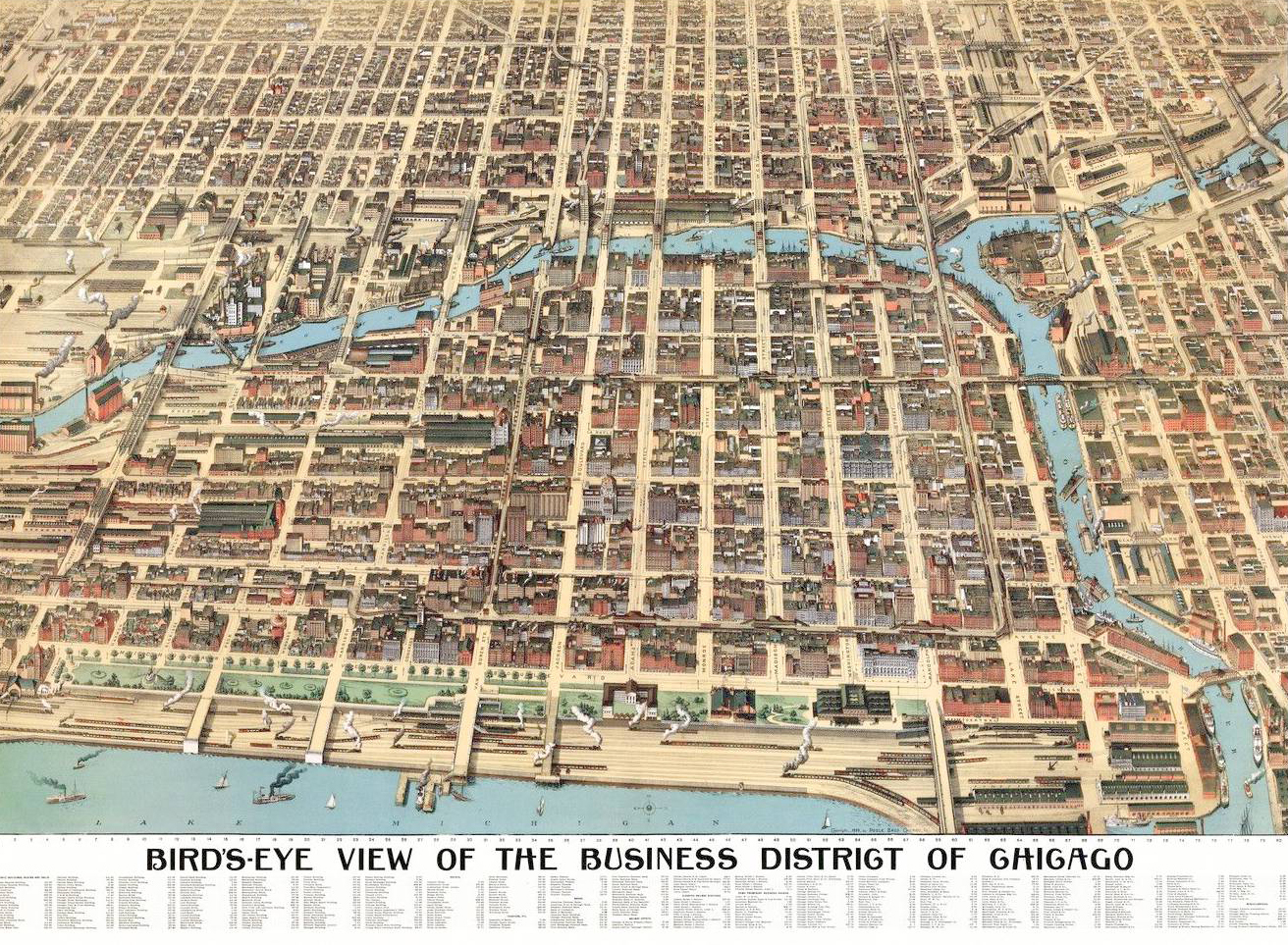

Why did the Loop develop where it is, and the skyscrapers along with it?

Leslie: The city was always about speculation, and you had a lot of money coming in that was betting on all of the goods that were moving through Chicago and being exchanged. Eventually, so many people come to kind of bet on those futures that they all need offices and the land in the Loop becomes a commodity itself that people start betting on. So that kind of drives a skyscraper culture. I think the other thing about it is that geographically it’s limited — there’s only a certain amount of land that’s actually in the Loop, and very early on there’s the perception that if you’re between the river and the lake, you’re downtown. If you’re across the river, you’re out in the Wild West.

Masengarb: When you look at businesses in the late 19th century, companies are typically clustered in neighborhoods where they make the product. The manufacturing plant is out in the neighborhood and the offices are next door. What we start to see happen as these businesses get bigger, they want to separate those two functions. Large companies with factories in the neighborhoods, like Pullman, start to locate their white collar office workers in separate places from their blue collar workers who are actually manufacturing the product.

Also, the companies want those office workers to be adjacent to the other types of businesses that they need to collaborate with or have contact with — like the post office, like their accountant, like their lawyers.

Why has the Loop remained Chicago’s business district and the skyscraper hub?

Leslie: I think there are a couple of reasons that it has not only stayed the skyscraper center of the city, but become much bigger. One is that all of the infrastructure in Chicago was designed to get people back and forth to the Loop. And so today, if you want to open an office where everyone in the city can commute easily, your choices are sort of limited. You’re going to put your building where all of the infrastructure goes. There is a perception about it like a kind of urban brand where to this day, 150 years later, if you’re in those 49, 50 square blocks, you’re downtown, and if you’re across the river or if you’re a mile north, you’re somehow not quite where all the action is. And I think that perception has continued to drive land prices which continues to drive a certain status to being in the traditional heart of the city.

Masengarb: I think addresses still matter, and building names still matter. “We’re moving our headquarters into the Merchandise Mart,” or “we’re moving our headquarters into Willis Tower.” Businesses are also trying to attract talent and the young talent says, “I want to live in the city. I don’t want to live in a far flung suburb where I have to commute by car and I can’t take my lunch outside along the river and I can’t go to a concert in Millennium Park after work and I can’t ride my bike or take the train.”

Will we see skyscrapers in other parts of the city in the future?

Leslie: The Loop will always be the Loop. It has all of the infrastructure, it has all the kind of associations with it. But it’s interesting to me that the part of town used to be known as Haymarket now is known as the West Loop. I think that’s telling, that’s the aspiration of developers in that part of town, to be thought of as an extension of the skyscraper district. You’re starting to see that skyscraper district kind of ooze out into the rest of the city from the [Loop], what will sort of always be the hub or the center of Chicago.

Masengarb: Experts say it would take something pretty dramatic to shift the center of the Loop as the center of gravity for Chicago both economically and physically. Either it would take some sort of economic disaster, natural disaster, or something huge. So I don’t think we’ll see a dramatic shift in things, but then of course there’s the sort of slow creep. These six corner intersections around the city, or those you know major even four corner intersections around the city, we’re going to start to see small versions of that growth continue or we’re going to get tall-ish buildings pop up. But I think in 50 years, we’re not going to see something dramatically different, we’re just going to see the push and the popping up of small skyscrapers.

More about our questioner

Growing up in the South Side neighborhood of Roseland, Keonte Brooks says he noticed that there were no tall buildings in his area.

“I’ve been to places like North Carolina and once Los Angeles, and every so often you would see a big building [outside of downtown],” he says. “But in Chicago it’s all downtown, nowhere else.”

Keonte says he was surprised to learn that part of the reason why all the skyscrapers are concentrated downtown has do with businesses wanting to be in close proximity to one another. He says he now has a newfound appreciation for the Loop.

“I’m pretty sure not too many people know why places look the way that they do,” he says. “So to know the history of downtown and how things come to be, yeah that’s a big deal.”

Keonte graduated in June from Percy L. Julian High School. He plans to attend Kennedy-King College in the fall to study broadcasting. Ultimately, he hopes to pursue a career in the TV industry.

“I like being in the spotlight,” he says.

Keonte’s question was collected at the Mikva Challenge annual showcase, where Keonte presented a project on bullying and suicide within his school.