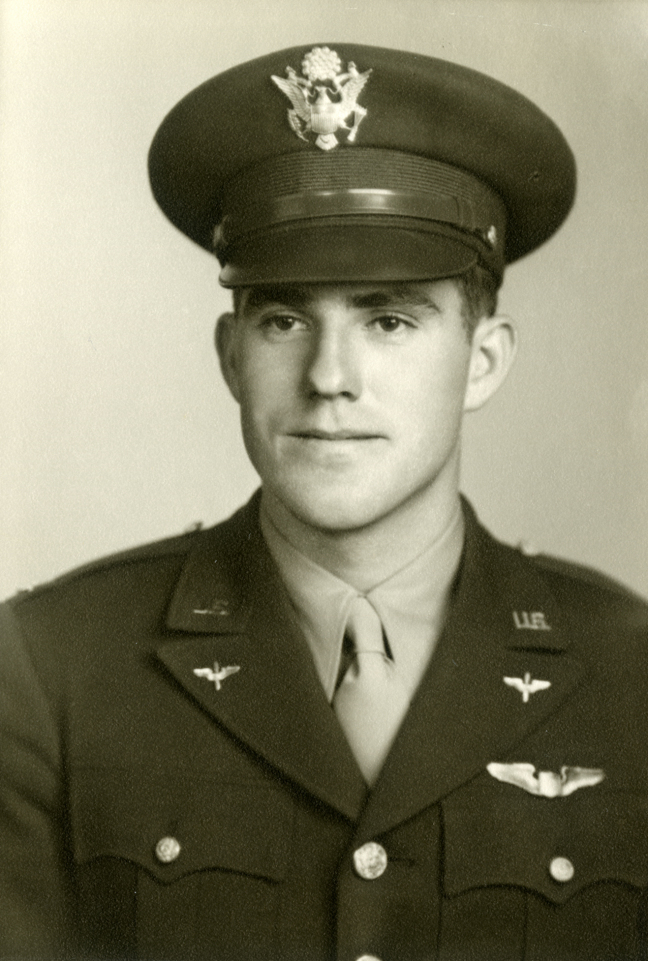

AMES, Iowa – William Howard Butler was a quiet man who left a lasting impact on his soldiers and all who loved him.

The 1935 Indianola High School yearbook shows Butler with the quote, “Because a man doesn’t talk is no sign he hasn’t something to say.” He was born March 31, 1919, to Thomas and Alice Corinne Butler.

Butler and two other former Iowa State students who died serving in World War II will be recognized during Iowa State University’s annual Gold Star Hall ceremony at 3:15 p.m. Monday, Nov. 12, in the Memorial Union Great Hall. This public event is free.

Former students are eligible for name placement in the Gold Star Hall — the war memorial in the university's Memorial Union — if they graduated from or attended Iowa State full-time for one or more semesters, and died while in military service in a war zone. As names become known, they are added to the wall and the soldiers are remembered in the university's annual ceremony.

Although Butler’s name was previously engraved on the memorial wall, he has not been honored in a ceremony. His remembrance has been made possible with information provided by family members Marilea Chase, John Pehrson and Marieta Grissom.

Butler’s path to Iowa State

Butler grew up on the family farm southeast of Indianola, helping his father raise cattle, hogs and horses and harvesting oats and hay. The discipline and patience he learned on the farm would prove valuable during his academic and military careers.

He attended a one-room schoolhouse in rural Warren County and passed the eighth grade exam early in order to attend high school with his sister. It was at Indianola High that he discovered his musical talents when he picked up the trombone.

After graduating from high school in 1935, Butler continued working at home on the farm. But his sister’s experience at Simpson College sparked his curiosity, and in 1940 he enrolled at Iowa State to study agricultural engineering.

While engineering attracted Butler to Iowa State, he also came with a plan to join the university’s ROTC program.

Honored for his heroism

Three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Butler enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force. After learning to fly at Thunderbird Field in Phoenix, Butler was appointed aviation cadet in May 1942. He received his commission and wings at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona. Butler graduated in the top 10 percent of his flight school class.

He joined the 13th Air Force in the South Pacific in April 1943, on the heels of the United States’ struggle to advance against Japanese forces in the first year of the war.

The tide slowly started to turn for American forces in spring 1943, though, thanks in part to soldiers like Butler. He completed 76 missions, helping to neutralize the Japanese threat in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. He was awarded the Air Force’s Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters, given “for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievements while participating in aerial flight.” Butler earned the rank of lieutenant in December 1943.

While he returned to the U.S. in April 1944 to serve as a flight instructor in Georgia, the ever-quiet man didn’t enjoy listening to himself talk as an instructor, and returned to action in November 1944.

He was assigned to the 16th Fighter Squadron of the 14th Air Force, whose mission was to defend air bases in southeast China. Butler earned the rank of captain while stationed at the Chengkung Airfield in China. It was here that Butler’s engineering expertise was put to use, as he built a windmill-like machine to wash clothes.

He even bought a horse while in Fiji, a call to his rural Iowa roots. In one of his final letters, Butler wrote to Iowa State’s alumni association asking for information on Iowa State’s farm operations course.

On July 16, 1945, Butler’s plane crashed shortly after takeoff in Chengkung, killing him instantly. His body was returned home to Warren County in 1948.