‘Tell me what you want – what properties you want.’

AMES, Iowa – Dhruv Raturi, an Iowa State University doctoral student and worm farmer, pulled clear, plastic boxes out from under the laboratory’s warming lights.

He held up a box, peered inside and pointed to a few worms digging in the potting soil. He also pointed to plastic pellets the worms couldn’t eat. But, he said, in these other boxes they’re eating this new stuff.

That new stuff is a plant-derived, biorenewable, biodegradable, agricultural lubricant. Cover seeds with it and they’ll glide through a planter evenly, uniformly. No friction. No jam ups. No planting problems. And, according to experiments by Raturi and Brad Swan, another Iowa State doctoral student, it will degrade in the soil and even hold some water.

Other commonly used seed lubricants – such as plastic pellets – aren’t nearly as safe for the environment.

That’s why Garrett Goins, the Ankeny-based manager for product safety and compliance for Crop Care products at John Deere, was recently looking at worms in Martin Thuo’s Iowa State materials science laboratory.

A few years back, the company was looking for new lubricants that would help seeds slide through planters. Could Iowa State researchers measure and compare what was already on the market? And could they come up with an alternative that was effective, yet non-toxic, biorenewable, biodegradable, easily manufactured and affordable?

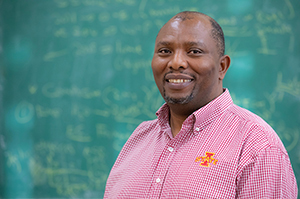

The project ended up with Thuo, an associate professor of materials science and engineering and recent recipient of a College of Engineering Schafer 2050 Challenge Professorship.

He’s been called a “metal whisperer.” He has expertise with heat-free solder and has co-founded a startup, SAFI-Tech Inc., that’s developing and marketing the technology for green electronics. (See video.) His lists of grants and publications wouldn’t suggest his lab is the place to develop new agricultural lubricants, but Thuo’s approach to problems made it the perfect place.

“We looked at this as a materials problem and one that’s easy to solve,” Thuo said. “Tell me what you want – what properties you want. I’m not going to give you a seed lubricant. I’ll give you a materials property.”

That’s exactly what he and his research group have done. Now there’s a pending patent through Iowa State's Office of Innovation Commercialization. And John Deere has a return on its research investment.

“Martin is very good at what he does,” said Goins. “He took a non-ag based approach to an ag problem and tried something totally new.”

A new product isn’t the only return the company will see from the project.

“We know an investment in Iowa State,” Goins said, “is also an investment in our future employee base.”

What would the village do?

Growing up in Juja, Kenya, about 20 miles from Nairobi – “not city or super rural” – Thuo and his playmates learned to make do.

“If you want a soccer ball, you have to make it with the materials you have – it was a ‘MacGyver’ spirit,” Thuo said, referring to the TV character who could save the day – and build just about anything – with a Swiss Army knife, some duct tape and a flashlight.

Juja also offered Thuo lessons in humility and working with people: “If you wanted to survive in the village, you needed people. You’re surrounded by nature and wildlife and mountains – you could see Mount Kenya.”

And there were lessons about himself: “Where I grew up was in the flight path from Nairobi Airport. I was fascinated by the flights going to different places.” The son of two teachers, “I was very curious. I wanted to understand the precise timing of the planes above and the natural world around me.”

That curiosity eventually led to studies at Thika High School, a boarding school where a teacher, Mr. Asava, inspired Thuo with his “way of explaining chemistry that was very beautiful.”

That led to chemistry, math and education studies at Kenyatta University in Nairobi. Thuo stayed on for graduate studies and then planned additional study in America. He applied to Iowa State because, in part, some of his Kenyatta professors had studied in Gilman Hall. But the 9/11 terrorist attacks closed America’s borders at that time.

Thuo detoured to Canada’s Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, where he came across a lab developing liquid crystal display technology.

“That’s where the world of materials opened up to me,” he said. “The people doing materials science are my people.”

He transferred to the University of Iowa for doctoral studies and worked on polymer membranes. One of his challenges was to simplify the synthesis of pharmaceutical precursors that required many steps yet produced very little. The project fused his chemistry, math and materials interest.

His solution: “Go back to the village.” Work with what you have. Find the clean and simple ways. Allow nature to do some of the work.

Next was postdoctoral work at Harvard University in Massachusetts where his faculty mentor, George Whitesides, reinforced the idea of simple, frugal innovation. “George was basically thinking about simplicity, but on steroids.”

Thuo still posts a quote by Whitesides on his research group’s website:

“Cheap, functional, reliable things unleash the creativity of people who then build stuff that you could not imagine. There’s no way of predicting the Internet based on the first transistor.”

Creativity on display

After a year as an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts, Thuo finally made it to Iowa State in 2014. Now he can tell the former Cyclones at Kenyatta that his lab is on the third floor of Gilman Hall.

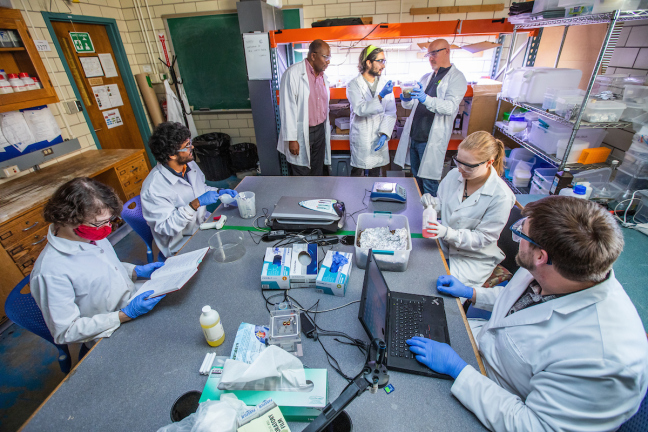

It’s a place where scientific creativity is always on display.

Thuo and his group have developed heat-free solder. They’ve printed electronics on rose petals. They’ve made “chameleon metals” that change surfaces in response to heat. With a bit of “metal whispering,” they’ve found a better way to recover precious metals from electronic waste.

And now, after two and a half years of work, they’ve invented a new seed lubricant.

What’s the source of that creativity?

“I think creativity is something that comes at the confluence of different disciplines,” said Raturi, the graduate student raising laboratory worms who has a background in physics. “Materials science and engineering is relevant to people from all disciplines and with different temperaments.”

In Thuo’s lab, there are often physicists, chemists, engineers, biologists and computer scientists all working together.

Alana Pauls, a second-year doctoral student who started working in Thuo’s lab as an undergraduate materials engineering student, called Thuo “our lighthouse.”

“When in need of guidance or support, he’s always there to help guide us back on track,” she said. “During my three years here, I’ve had the ability to grow as a researcher, but also as an individual, a team player and a leader.”

W. Samuel Easterling, Iowa State’s James L. and Katherine S. Melsa Dean of Engineering, noted Thuo’s innovation, collaboration, outreach and the opportunities he creates for students: “It is very exciting and rewarding for our engineering students to work in this hands-on environment with Dr. Thuo and gain real-life experiences that will help advance their future careers.”

Ian Tevis, a former postdoctoral researcher in Thuo’s lab who’s president and chief technology officer of the SAFI-Tech startup (which takes its name from the Swahili word for clean), said Thuo “has always been a visionary and a dreamer.”

“He believed we could make this new technology and it would have a real impact on how electronics are made today,” Tevis said. “Martin would say, ‘Do this.’ I’d say, ‘It’s impossible.’ Martin says, ‘Do it anyway.’ And Martin was right.”

And what does Thuo say about the creativity in his lab? Mostly, he talks about his students and collaborators.

“I’m trying to encourage my students to think and seek collaborations,” he said. “The most valuable resource we have is somebody giving us a chance to solve their problem. And every problem allows us to think a little differently or learn from those who have expertise we don’t have.”

What’s next in Thuo’s lab?

“There are challenges in microelectronic fabrication, smart catalysts for energy, material supply chains and materials for health care,” he said. “The challenges are endless, and so are the opportunities for creativity.”