Christina Gish Hill, associate professor of anthropology and American Indian studies. Larger image. Photo by Christopher Gannon/Iowa State University.

AMES, Iowa — A new book highlights collaborations between the National Park Service and Native tribes, offering pathways to develop long-term relationships. The authors, representing Native and non-Native voices from the National Park Service, tribal governments and academia, say deep listening, emotional commitment, mutual respect and patience are key.

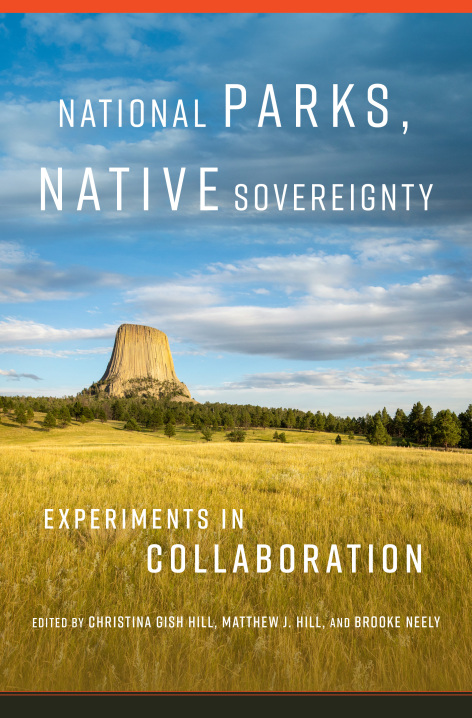

One of the editors and contributors for “National Parks, Native Sovereignty: Experiments in Collaboration” is Christina Gish Hill. The associate professor of anthropology and American Indian studies at Iowa State University says relationships between tribes and the National Park Service historically have been fraught. Native people were often removed from land they considered sacred in the process of developing national parks and monuments.

“Our national parks are Indigenous lands, and those spaces are profoundly important to the Indigenous nations that called those landscapes home. While collaboration with the National Park Service is an imperfect form of repair work, it’s an entry point,” says Gish Hill.

She says more National Park Service staff and tribal governments have recognized the need to engage in recent decades, and amidst the challenges, there are success stories. This includes a recent agreement that allows Cherokee citizens to harvest traditional plants within the Buffalo National River Park in Arkansas and the co-management of Grand Portage National Monument in Minnesota between the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwa and National Park Service.

“It’s a powerful thing to create space where Indigenous people can have a say, have a voice in the management and interpretation of their own important landscapes. Collaboration can build relationships that benefit everyone,” says Gish Hill.

Along with the case studies, the book includes interviews with Gerard Butler, a member of the Mandan-Hidatsa Tribe and the first Indigenous National Park superintendent; Max Bear, the tribal historic preservation officer for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma; and Lance Foster, the tribal historic preservation officer for the Ioway Nation. Foster discusses the Ioway Tribal National Park, which was established by the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska in 2020 and will open to the public in 2025. The park is located within the Ioway Reservation, on a forested bluff over the Missouri River.

Gish Hill says the book’s concept emerged from conversations with the other editors, Matthew J. Hill and Brooke Neely. All three scholars had worked together on an ethnographic overview and assessment about Mount Rushmore for the National Park Service from 2016 - 2019. Their goal was to cover the monument’s entire history, including the significance of the Black Hills for Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho people in relation to Mount Rushmore.

“After that project, we talked about how it would be really helpful to have a book that offered best practices for collaboration, and we knew there was a lot of interest, especially from people who work in museums and at state and national parks,” says Gish Hill. “After presenting at the National Council on Public History, many in the audience told us that they want to reach out to Native people and tribal governments, but they don’t know where to start.”

Lessons learned through experience

In her chapter “Reciprocal Respect: Lessons Learned about Collaboration,” Gish Hill reflects on her experience with the Mount Rushmore project, emphasizing the importance of going through proper channels before conducting research. On the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, this meant connecting with the tribal historic preservation officer and presenting the project to the cultural committee.

Conversations with elders and government officials during that presentation led Gish Hill to tweak and expand some of her interview questions. It also offered an opportunity to discuss compensation and culturally appropriate gifts for participants, which Gish Hill says “honors the value of the knowledge they share.” They decided on a small gift card and a braid of sweetgrass at the Northern Cheyenne reservation and a gift card and a pouch of tobacco at the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation.

Gish Hill also describes how using consent forms before conducting interviews can build trust. The language in the document makes clear that participants can “share as much or as little as they want.” Some participants said they did not want their voices recorded but were open to Gish Hill taking notes. Others wanted to share their thoughts without having them recorded in either format.

The consent form also lets participants know that the “content of their interview belongs to them,” says Gish Hill.

“I always try to give transcripts to people to get their feedback because the people I’m interviewing are basically the traditional scholars of their own culture, and their input on the narrative is essential to an accurate representation,” says Gish Hill. “Academics polish their writing before it goes out into the public sphere. I want participants to have the opportunity to be able to do the same.”

While the goal of the book is to provide resources for people who work in the National Park Service, tribal governance or historic preservation, Gish Hill says it's written for a general audience.